2,000-year-old wine and the uncanny immediacy of the past

Why artifacts like the Carmona Wine Urn, the Pazyryk Rug, and the Sword of Goujian are so important

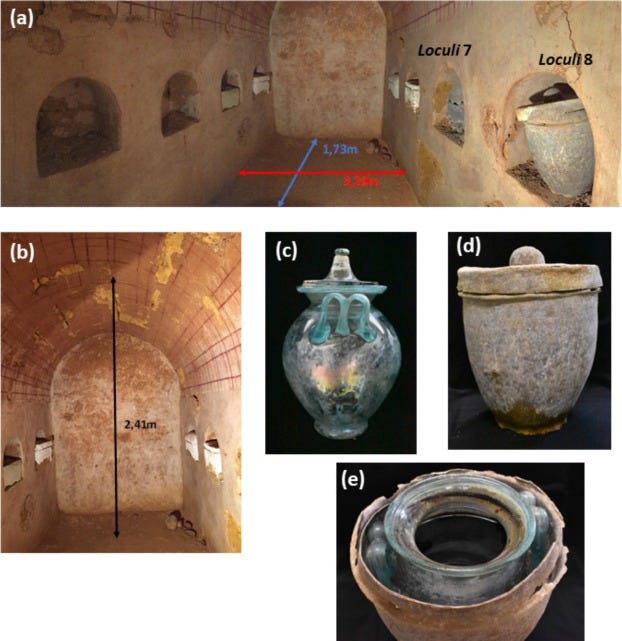

In 2019, construction workers in Carmona, Spain uncovered something remarkable underneath a very old house: an access shaft that led them to a Roman tomb which had remained perfectly sealed for two thousand years.

The tomb itself was striking enough: a vaulted chamber decorated with geometric patterns in red and ochre, its walls lined with eight niches for funeral urns. But it was what they found in one of those niches that would prove extraordinary. There, nestled in a lead case, sat an iridescent glass urn containing cremated remains — and five liters of a mysterious reddish liquid.

Even before they analyzed this liquid, the archaeologists (whose full report in the Journal of Archaeological Science can be read here) knew they were dealing with something special. The tomb’s preservation was remarkable. Its painted decorations were still vivid, and among its contents were pieces of Baltic amber, fragments of ancient fabric, and a crystal flask containing a perfume that turned out to be patchouli.

But a glass jar that was “filled to the brim” with an intact liquid from the age of Augustus? This seems almost impossible. And yet there it was.

Dating back to the first century CE, the incredibly well-preserved liquid turned out to be the oldest wine ever discovered — three centuries older than the previous record holder, the Speyer wine bottle, which was also recovered from an ancient Roman tomb back in the 1860s.

I love this kind of thing for several reasons. For one thing, I’m fascinated by the intersection between science, technology, and history in the sort of discovery. To make sense of something like the Carmona Wine Urn, you need to triangulate between the results produced by exquisitely complex machines (in this case, a “Sciex 7500 QTrap Triple Quadruple analyser,” a form of mass spectrometer), the careful scientific work of archaeologists, and the archival research of historians.

In that sense, it’s similar to the work that was done to determine that two individuals in 17th century Italy likely consumed coca leaf at some point prior to their death, a finding I wrote about a few months ago:

But what I love about this kind of artifact is that you can literally see, smell, and (conceivably, though certainly not advisedly!) even drink it.

After all, the “cocaine” residues found in the preserved brain tissue of those two people found in early modern Milan were just invisible traces of chemical markers.

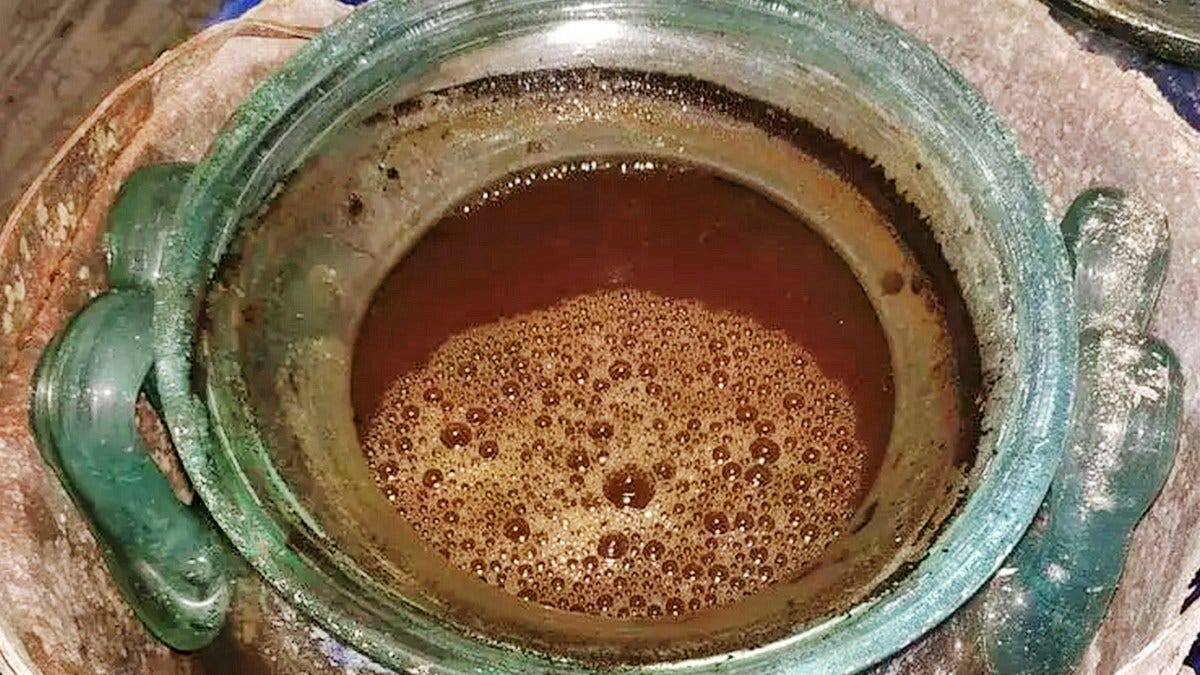

By contrast, this is what the archaeologists found in the glass jar at Carmona:

Chemical analysis has confirmed not only that this is indeed wine, but that it is specifically a white wine which bears striking similarities to the fino sherry wines still being made in the region around Seville in southern Spain where the tomb was discovered.

This is interesting for all kind of reasons, most of them having to do with Roman archaeology, the history of alcohol and drugs, and the like.

But I think you should care for another, bigger reason.

The Carmona wine belongs to a special category of historical artifacts — freakishly well-preserved objects that collapse the distance between past and present in uniquely visceral ways. For me, at least, these objects make the past feel immediate in a way that nothing else can.

And why does that matter?

Well, because one of the greatest blind spots of our species is a failure of imagination about the lives of the 100+ billion humans who lived before us. I find that my students tend to think of the past in terms of great artworks and great historical figures — boiling the entire 16th century down to Cortez, The Prince, and the Mona Lisa, for instance.

I can’t really blame them for seeing the past this way. Historical experience tends to be preserved — and certainly tends to be taught — as a succession of famous cultural products that serve as metonyms for a larger story. The three millennia of ancient Egypt become personified by the Great Pyramid and King Tut’s death mask; the Ming Dynasty collapses into a blur of blue-and-white porcelain; the whole of Elizabethan England is remembered chiefly from the rather distinct perspective of a single person named William Shakespeare.

This “metonymic approach” is, honestly, really helpful for teaching. I use it all the time in my world history surveys. But it doesn’t really capture the texture of everyday life in the past. Precisely because these works are so exceptional — and hence so well-studied — we tend to place them as part of a nebulous “cultural heritage of humanity” rather than as specific products of a time and place.

That’s why I love it when archaeology presents us with a different type of iconic artifact: objects that offer a glimpse into the visceral reality of past lives. The Carmona wine urn belongs to this select group, alongside artifacts like the 2,500-year-old Pazyryk carpet which Soviet archaeologists discovered in a Siberian tomb, its blood reds and acid greens still vibrant after over two millennia frozen in ice:

Or the Roman bread carbonized by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, complete with the baker's stamp still clearly visible on its crust:

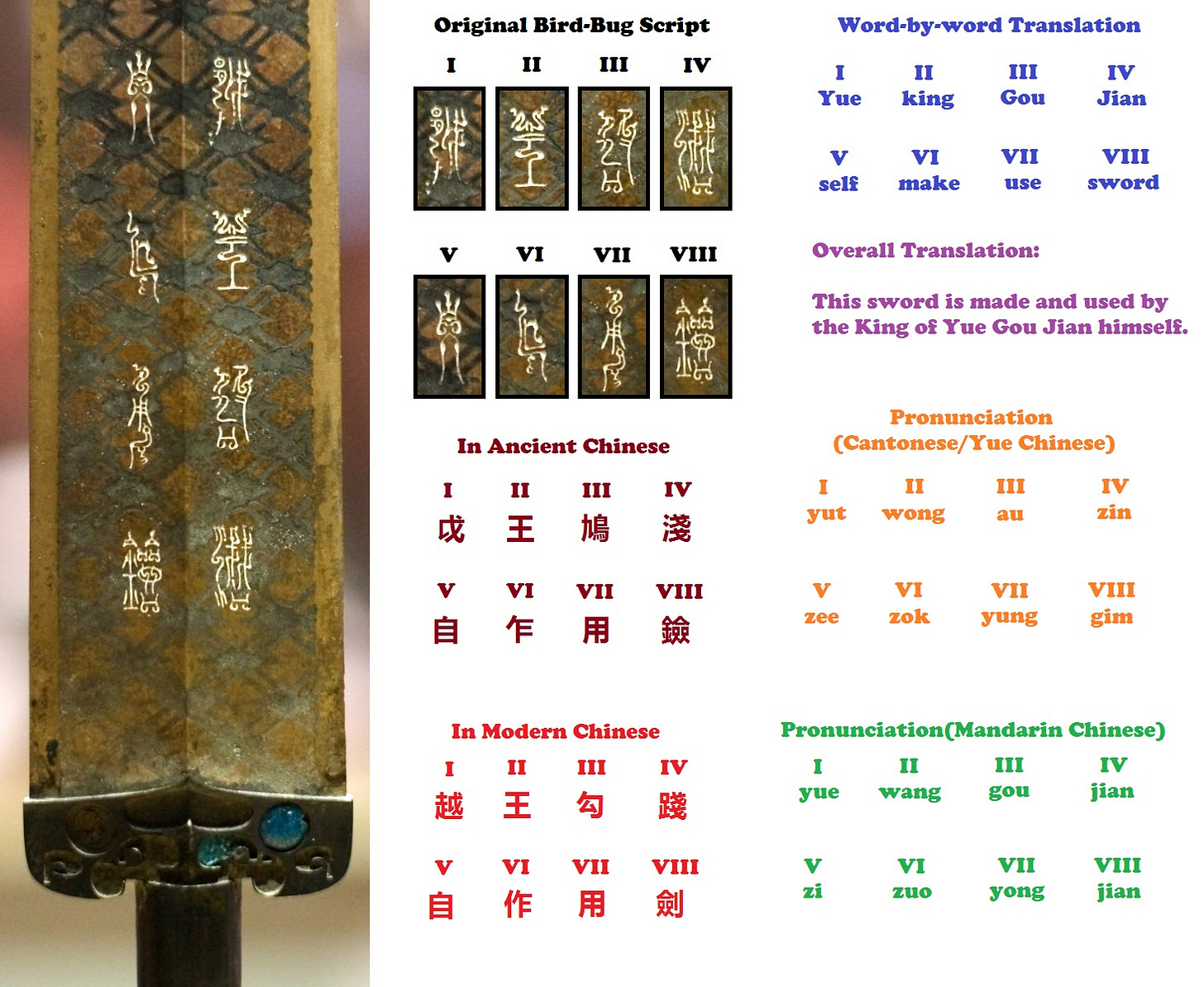

Or what to my eyes is one of the most shockingly well-preserved ancient artifacts ever found: the Sword of Goujian, which dates back to the Spring and Autumn period of ancient China (771 to 476 BCE) and which was found during an archaeology survey of an aqueduct of the Zhang River in 1960s China.

Not only is it almost entirely free of rust or tarnish, despite having spent centuries underwater. It’s still sharp enough to knick your finger.

Even more remarkable, the inscription on the sword identifies, by name, the person who once held it nearly 2,500 years ago: Goujian (勾踐), the King of the State of Yue.

I still can’t quite believe this is real. It’s like something from the J.R.R. Tolkien universe that has entered the actual historical record. (Look at those gold-inlaid ideographs!) Admittedly, a sword forged for a king is a far cry from a truly everyday item like the Vesuvius bread loaves. But what these objects all have in common is that they are so untarnished by time that we can actually imagine them being used.

These ghostly traces of ordinary life do something that even the greatest works of art cannot. They remind us that the past wasn't just a parade of famous names and grand events. It was populated by people who drank wine, broke bread, wielded tools, and walked on carpets, just as we do.

If you’ve read this far, please consider a paid subscription. Reader support is essential for allowing me to write Res Obscura — one of the few places online with ad-free, original longform historical writing. You’ll receive the same weekly posts as free subscribers, plus:

Occasional special posts/works in progress

Quarterly reader Q&As

The good feeling of financially supporting something being offered for free

Weekly links

• “Strontium isoscape of sub-Saharan Africa allows tracing origins of victims of the transatlantic slave trade” (Nature)

• “Following Gödel, we can interpret the dust particles as galaxies, so that the Gödel solution becomes a cosmological model of a rotating universe. Besides rotating, this model exhibits no Hubble expansion, so it is not a realistic model of the universe in which we live, but can be taken as illustrating an alternative universe… these observations improved continually up until Gödel’s death, and he would always ask ‘Is the universe rotating yet?’ and be told ‘No, it isn’t.’” (from the Wikipedia page for Gödel's metric)

• “I am arguing that it is likely that the men buried in the princely burials at Prittlewell and Sutton Hoo mound 1 served, with a group of their contemporaries, as cavalry soldiers in the Foederati recruited by Tiberius in 575 in the wars with the Sasanians on the eastern front.” (“Sutton Hoo and Syria: The Anglo-Saxons Who Served in the Byzantine Army?” a fascinating new article in The English Historical Review)