Res Obscura Newsletter: December, 2019

Note: this was exported from Mailchimp.

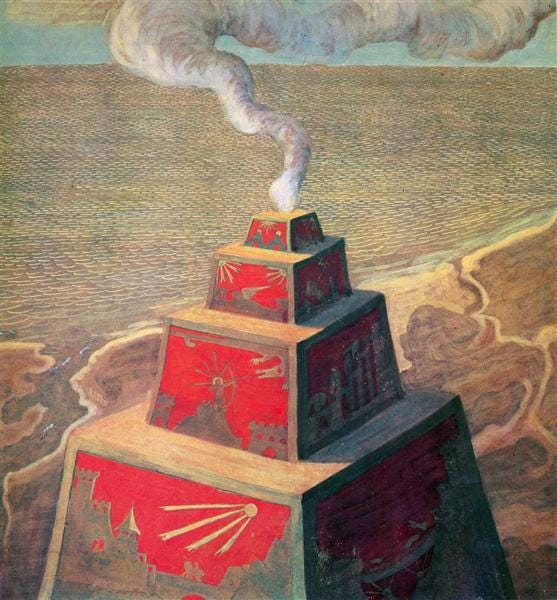

That's a 1909 painting called "Altar."

It's by someone I learned about just this month: the Lithuanian composer and artist Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis (1875-1911). His paintings and music evoke a mysterious feeling that has stuck with me throughout these intensely rainy weeks in California. Some look a bit like the covers of alternate-reality C. S. Lewis or Tolkien books; others are visionary artworks in the style of William Blake.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Čiurlionis suffered what seems to be the required fate of the visionary artist in the twentieth century: he died young (only 35!) in 1911, after being institutionalized for depression.

As far as I can tell, he was a genius. An online gallery of his work can be found here, and his compositions abound on Youtube.

As a reminder, you're receiving this because you signed up for the Res Obscura newsletter, an offshoot of the history blog Res Obscura. It started out as a venue for posting oddities and links relating mostly to early modern history, but is now more in the style of newsletters like Robin Sloan's Year of the Meteor, Ben Tarnoff's Metal Machine Music, or Sarah Warner's Early Printed Fun.

Books I'm reading this month

Tavis Coburn, book jacket design for Francis Spufford's Red Plenty, commissioned by Faber & Faber, 2010.

Francis Spufford's Red Plenty is a book I'd been hearing about for years, but put off reading: I always assumed that a heavily-researched experimental novel about Soviet economics wouldn't exactly be a fun read.

I was completely wrong.

So far, Red Plenty is one of the most engaging novels I've read in years. And although it isn't a traditional history – even the characters based on real figures are heavily fictionalized – it's one of the few novels that I can imagine serving as the core reading for a history class. The footnotes are the real deal, as are the tiny details of life in the Kruschev era. Some of those details seem infinitely far away, like the advertisements for Soviet champagne ("Life has become better, more cheerful!") or the workings of the Svetlana Vacuum Tube Factory.

Elsewhere, however, Spufford's vision of the USSR circa 1960 is weirdly contemporary. In the dream of Spufford's Soviet economist, you barely have to squint to see the agenda of the more utopian wing of Silicon Valley's AI boosters: "He was lucky enough to live in the only country on the planet where human beings had seized the power to shape events according to reason... Seen from plenty, now would be hard to imagine. It would seem not quite real, an absurd time when, for no apparent reason, human beings went without things easily within the power of humanity to supply, and lives did not flower as it was obvious they could. Now would look like only a faint, dirty, unconvincing edition of the real world, which had not yet been born. And he could hasten the hour, he thought, intoxicated."

+ Red Plenty also lead me to find this footage of part of the famous 1959 "kitchen debate" between Kruschev and Richard Nixon. The body language is fascinating to watch, as is the eerie, slightly offset look of the early color television technology being used, which Nixon keeps proudly referencing.

A publicity image from the infamous "Little Albert" experiment, 1920.

Rebecca Lemov's The World as Laboratory is a splendid history of the rise of "human engineering," an interdisciplinary effort of the early twentieth century driven by a strange blend of American optimism and paranoia. It's a story about behavioralist experiments with humans and animals, many macabre and cruel, others utopian.

Lemov writes: "Eventually the more generous impulses of social science to connect, to make contact with, to juxtapose, to see more clearly, and to invent—to 'treat life not as something given but as something to be shaped'—were largely transformed into their opposite: to winnow down, to prevent, and to build systems of control, adjustment, and persuasion, escape from which would be ever more unlikely." Lemov's portrait of scientific creativity being repurposed as a market-driven tool of control has obvious echos in the present – but I wonder whether it calls back to a deeper past as well? I'm thinking of the Royal Society's ties to the Royal African Company, or William Max Nelson's paper on Enlightenment scientists and "racial engineering" in the slave societies of the eighteenth-century Caribbean.

+ One of the creepier links between twentieth century human engineering and Enlightenment-era racial science: apparently the behavioralist John B. Watson, of Little Albert experiment fame (see image above), looked back on his career and concluded, "I sometimes think I regret that I could not have a group of infant farms... someday it will be done, but by a younger man." Yikes.

Shorter reads

• In The New Yorker, Casey Cep writes about the "real genius" of Thomas Edison: not inventing, but improving.

• Alexis Madrigal on the Apollo landing computer: "To maximize the built-in architecture, Hamilton and her colleagues came up with what they named 'The Interpreter'—we’d now call it a virtualization scheme. It allowed them to run five to seven virtual machines simultaneously in two kilobytes of memory."

• A 1999 essay about cybernetics and "the countercultural roots of computer culture." Dated, but in a way that makes it more interesting to read, not less.

• "Metagenomic analysis of a blood stain from the French revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat (1743-1793)." Talk about a macabre article title. I can't decide if this kind of research isn't much more than a parlor trick – after all, knowing precisely what skin disease Marat suffered from doesn't really amount to much – or the start of a fascinating new subgenre of historical research. Certainly, reliable genomic analysis of, say, the contents of antique drug jars could help answer some questions. But more importantly, what new questions could it generate?

What I'm writing

I just finished a draft of an op-ed arguing for the legalization (as opposed to just the decriminalization) of psilocybin, peyote, and related psychedelic compounds.

Also thinking through a piece on OpenAI's text-generation system GPT-2 and its implications for history writing. Here are some examples of the algorithm's take on famous historians. I want to stress that these are not real quotations, they are 100% generated by a computer! You can experiment with it here. To obtain these, I fed in a randomly selected sentence fragment from each author, and got the following results:

Herodotus: "For the Thracians and Dorians both have an alphabet of their own and the Minyai who dwell on the island of Cyzicus have a peculiar system, being acquainted with a kind of Phoenician language, though none of them have written with letters. So Hellas was by far the better off for her different learning. But to the Greeks her words were bitter and full of bitterness to be spoken, and at length they urged the Greek bards to write down their speech and write down their poems for them."

Edward Gibbon: "However loudly or angrily men may praise or condemn the worship of the gods, the final decision of the multitude is never on the side of the magistrate or the philosopher. The attempt to banish the priesthood from the republic, by obliterating the most ancient institution of the commonwealth, may be justly censured by those who are the most universally affected with the glory of the public religion. It was only by the terrible conflict between reason and superstition that the rights and liberties of the subject were preserved from the tyranny of any one or all of them."

And, for fun, Donna Harraway: "Into this void must come cyborg scientists who set out to rethink the biological problems posed by the human condition and who find ways to project a consciousness that is human-ish. In this post-human world, the scientist must be the master of social theologies and the ideologist of myth. Conversely, we are not happy with the burlesque and messianic hypostatization of that last little bit of self-consciousness that remains intact, hanging on in the brain from unconscious memory forms."

+ So... how will machine learning tools like GPT-2 change grading, and academic assignments in general? There's this, on "AI and the Future of Cheating," but it's pretty thin. Anyone reading this know of any work on this topic?

My book!

Last week I finally laid hands on a real, physical copy of my book The Age of Intoxication: Origins of the Global Drug Trade. It's not officially published until December 20, but you can order a copy right now now via Indiebound, Amazon, or the University of Pennsylvania Press. Also, if you're interested in reviewing it, please email me and I can have Penn send you a review copy.

Thanks for reading, and happy holidays.

- Ben