Before psychedelic therapy for wartime trauma, there was narcosynthesis

Notes on using AI to analyze three World War II-era films about drugs and PTSD

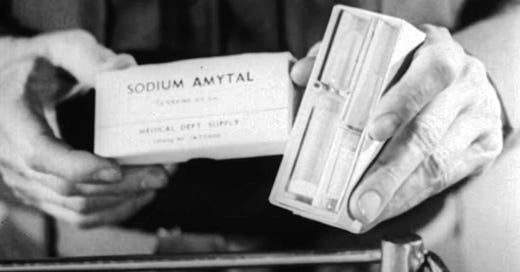

When writing Tripping on Utopia, my book on the history of psychedelic science in the 20th century, I found an enormous amount of material from the 1940s relating to a kind of therapy I’d never heard of before. It was called narcohypnosis or narcosynthesis. In essence, this involved the use of potent sedatives — especially sodium pentothal and sodium amytal — to put patients in a prolonged dream-like state. Psychiatrists of the era hoped that this would allow them to process, or “synthesize,” trauma from repressed memories of violence or conflict.

I had been working on a post about a different subject for this week, but given recent events, I’ve been thinking instead about war-related trauma. Psychedelic therapy has enormous promise as a treatment for PTSD, helping patients process traumatic memories related to experiences of violence. This has been documented in scientific studies, reported widely in the news, and become a major part of the bipartisan effort to legalize psychedelic therapy led by proponents like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

What’s often forgotten is that psychedelic therapy for PTSD was directly inspired by an earlier treatment for trauma that emerged out of World War II: narcosynthesis.

Below, I’ll summarize what narcosynthesis was all about, and then discuss the potential for a new AI-assisted approach for drawing lessons from this complex history.

A (failed) chemical short cut

The history of trauma as a psychiatric concept dates back to the generation before Freud. The early history of PTSD begins with pioneering psychiatrists of World War I like W.H.R. Rivers (whose work with shell-shocked soldiers is beautifully rendered in fictional form in Pat Barker’s novel Regeneration). But narcosynthesis was a distinctly World War II-era treatment. It was developed and spread by U.S. military psychiatrists who faced the impossible task of rapidly treating soldiers suffering from what was, at the time, known as “combat fatigue” or “battlefield neurosis.”

For a brief period of a few years during and after the war, narcosynthesis seemed poised to enter the mainstream of American society. An article on the topic in Life magazine in February of 1945, for instance, claimed that narcosynthesis “may conceivably revolutionize psychiatric practice.”

Here’s how Life summarized the basic idea:

Obviously, the technique of psychoanalysis is out of the question in the [military] services and because of time and expense it is out of the question for most civilians as well. But in the Army and Navy today a new technique called narcohypnosis is reported to have given, in a matter of hours, results comparable to prolonged analysis. Psychoneurotic cases, so badly shocked by battle experiences that they cannot talk about them, have been given injections of the drug sodium pentothal. This induces a dreamlike state in which the barriers to memory are removed. The patient then releases the suppressed material … If narcotic drugs can indeed accomplish the equivalent of months of free association in psychoanalysis, then psychiatry will be more nearly at the service of the common man. He badly needs it, not only for the immediate healing of his psychosomatic scars, but for the future of civilization.

If that sounds similar to psychedelic therapy, there’s a good reason: it directly inspired it.

One example of this link is right there in the Life article I just quoted. The article goes on to describe the work of a young Army psychiatrist named John P. Spiegel, one of the leading proponents of narcosynthesis. In the early 1960s, Spiegel — a fascinating character who was the subject of an excellent profile by his granddaughter Alix Spiegel in This American Life — would serve as the faculty mentor for Timothy Leary’s psychedelic research project at Harvard. And well before that, 1950s-era research with psychedelics like LSD and mescaline was deeply shaped by wartime narcosynthesis: Spiegel was far from the only scientist with a foot in both worlds.

But that’s a story for a different day (one that’s covered in my book). Suffice to say, narcosynthesis failed to revolutionize psychiatry. It was a stopgap therapy developed to return soldiers to the battlefield in the shortest possible time, not a lasting cure.

For the rest of this post, I’m going to proceed from two assumptions:

Narcosynthesis failed because there is no “short cut” to healing from trauma. Insofar as effective psychedelic therapy draws on lessons from narcosynthesis, it’s mainly about what not to do. For instance, effective psychedelic treatments for PTSD tend to include multiple followups over a long period, whereas narcosynthesis attempted what L. Ron Hubbard — who was, himself, a proponent of a modified form of narcosynthesis — once called “the one-shot clear.”

Today, AI therapy is poised to become the narcosynthesis of the 2020s — a supposedly faster and cheaper replacement for “real” therapy. Chatbots based on GPT-4 are already being proposed as a new short cut to healing.

My personal belief is that using large language models as therapists is a naive and potentially dangerous misuse of a powerful tool.

But there’s another use for LLMs like GPT-4 and Claude that I believe could be helpful for researchers and practitioners in the field of psychedelic-assisted therapy today. Perhaps they can help us synthesize the enormous amount of historical material relating to past treatments for PTSD and to draw important lessons from it.

In other words, maybe they can synthesize the history of narcosynthesis itself.

A (possibly effective) research short cut

What do I mean by that? One thing I learned from writing Tripping on Utopia is that there’s a huge amount that contemporary clinical practitioners can learn from the history of psychiatry. But so much of that material is buried in archives that clinicians and researchers seem mostly unaware of. It’s a different story for historians of medicine, who have made extensive use of those archives. But we tend to approach this material in a different way. We don’t think in terms of actionable insights, and we typically write for other historians.

Can AI help? As I wrote about last week, the AI system Claude is a powerful tool for conducting historical research because of its very large context window, which allows it to analyze tens of thousands of words at a time. My previous work on this was about translation:

But what happens when we feed Claude the transcripts of three documentaries about narcosynthesis, then ask it to draw connections with psychedelic therapy?

I started with a film that is likely the most famous historical source relating to narcosynthesis. It’s also one that came close to being lost to history forever: the legendary director John Houston’s documentary Let There Be Light (1946).

The film was produced in 1946 and was intended to educate the public about post-traumatic stress disorder and its treatment among returning veterans, but its unscripted presentation of mental disability caused the U.S. government to suppress the film, and it was not released until the 1980s.

My method was simply to copy and paste Youtube’s automatically-generated transcript of the film, then ask Claude to summarize its key points.

I then asked Claude to pull out specific quotes that may have some connection to the subsequent history of psychedelic therapy, along with a timestamp so I could check the original to ensure accuracy:

The results were flawed but intriguing. Claude was able to deduce the context of a quote (such as “psychiatrist hypnotizing patient” and “narrator”) without having access to any data that showed this — it was simply given a raw transcript with many errors and no indication of the setting or speaker. I’ve linked to the transcript here, as a Google Doc.

Claude was also able to summarize the complete transcript of the 40+ minute film in simple bullet points:

I then tried “feeding” Claude the transcript of two other World War II-era films documenting narcosynthesis, and asked it to “make a bullet point list of key takeaways from these three films that illustrate the most important lessons psychedelic researchers of today should learn in terms of the mistakes of narcosynthesis.”

It returned the following:

Uncontrolled abreaction can retraumatize rather than heal if not carefully guided.

Narcosis dulls emotions rather than amplifying them for release.

Plunging patients into distressing memories risks harm without proper preparation and integration.

Cathartic emotional discharge does not necessarily provide lasting benefits without insight.

Lack of consent and alignment with participant motivations can breed resentment.

Heavy sedation prevents authentic engagement needed for working through trauma.

Drug-induced suggestibility can lead to false memories and regression without safeguards.

Iatrogenic harm is possible without adequate screening for contraindications.

Suggestion therapy requires nuance to avoid unintended consequences.

Drug effects alone are insufficient without psychological integration work.

Patronizing "we know best" stances undermine participant agency and autonomy.

Context, trust, and integration are key; drugs do not replace human relationships and wisdom.

I thought this was a pretty impressive high-level synthesis. The key thing here is that this kind of analysis — pulling out key quotes, analyzing them in relation to a given topic, and summarizing the main takeaways — can now be done at scale with not just three historical sources, but (potentially) three hundred.

Will this sort of thing actually yield meaningful insights for psychiatrists and others working to treat PTSD today?

It’s hard to say. Certainly, there will always need to be a human in the loop to make sense of these findings, and, of course, to fact check them. But I am excited by the possibility for a tool like this to assist researchers in finding meaningful insights in the archive. Historians tend to be conservative about their methods, but I’m in favor of anything that could make historical research more accessible for people in fields that would genuinely benefit from revisiting the lessons of the past — and especially the mistakes of the past. I suspect that psychedelic therapy for PTSD is one of the more impactful such fields.

Weekly Links

The three films discussed here: “Let There Be Light” (1946), “Combat Exhaustion” (1943), and “Psychiatric Procedures in the Combat Area” (1944).

Danielle Carr’s great New York magazine feature article on the more recent history of trauma as a psychiatric diagnosis.

A Dictionary of Modern Slang, Cant, and Vulgar Words (1860) (Public Domain Review)

Five 1,500-Year-Old Gold Foil Figures Unearthed in Norway (Archaeology)

If you’d like to support my work, please pre-order my book Tripping on Utopia: Margaret Mead, the Cold War, and the Troubled Birth of Psychedelic Science or share this newsletter with friends you think might be interested.

As always, I welcome comments. Thank you for reading.

"For instance, effective psychedelic treatments for PTSD tend to include multiple followups over a long period, whereas narcosynthesis attempted what L. Ron Hubbard — who was, himself, a proponent of a modified form of narcosynthesis — once called “the one-shot clear.”

Today, AI therapy is poised to become the narcosynthesis of the 2020s — a supposedly faster and cheaper replacement for “real” therapy. Chatbots based on GPT-4 are already being proposed as a new short cut to healing."

These arguments against one-shot treatments are arguments for AI therapy. No one is proposing that you'll just talk to a chatbot for half an hour (and no one does that - whether it's today's GPT-4 bot or AI Dungeon 2 or Replika or Xiaoice or ELIZA back in the mists of time, pretty much all uses of chatbots for therapy-esque purposes reports that many users will spend a *huge* amount of time on them). All proposed uses, like your SciAm link, assume that users will be talking to the therapy bots a huge amount indefinitely - and that's why they work, because a bot can talk to you for hours a day anywhere anytime forever for a few bucks of electricity a month (and rapidly decreasing plus rapidly getting better), while a trained psychotherapist would cost a fortune and then burn out and have to be replaced by a worse & more expensive therapist.