Do painters subconsciously paint themselves into their work?

The Renaissance history of automimesis, and a proposal for research

When I was 12 or 13, I spent a lot of my free time reading art books at the library. It was there that I first came across an idea dating back to the Renaissance.

Ogni pintore dipinge sé: “every painter paints themselves.”

The earliest attributed source for the quote is Cosimo de Medici (1389-1464), the Florentine powerbroker and arts patron. It seems to have rapidly become a proverbial expression, capturing something of the ambient folk wisdom of Renaissance Italy.

Leonardo da Vinci, for one, discussed it at length in his Treatise on Painting. The tendency of painters to mirror themselves in their art was, da Vinci believed, one that revealed much not just about how the painter looked, but how they thought.

Art historians have written about this idea, which they call automimesis, for well over a century. They’ve uncovered a surprisingly complex history involving Aristotle’s theory of personality and Neo-Platonic philosophy (here is a good article on the topic, and here’s a new book on “the Involuntary Self-Portrait”).

But for now, a quick example so you can see what I mean. Below is a self-portrait by the Florentine painter Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510):

What do we see? Ringleted hair; a prominent chin; “cupid’s bow” lips; hooded eyes; and light, sardonically arched eyebrows.

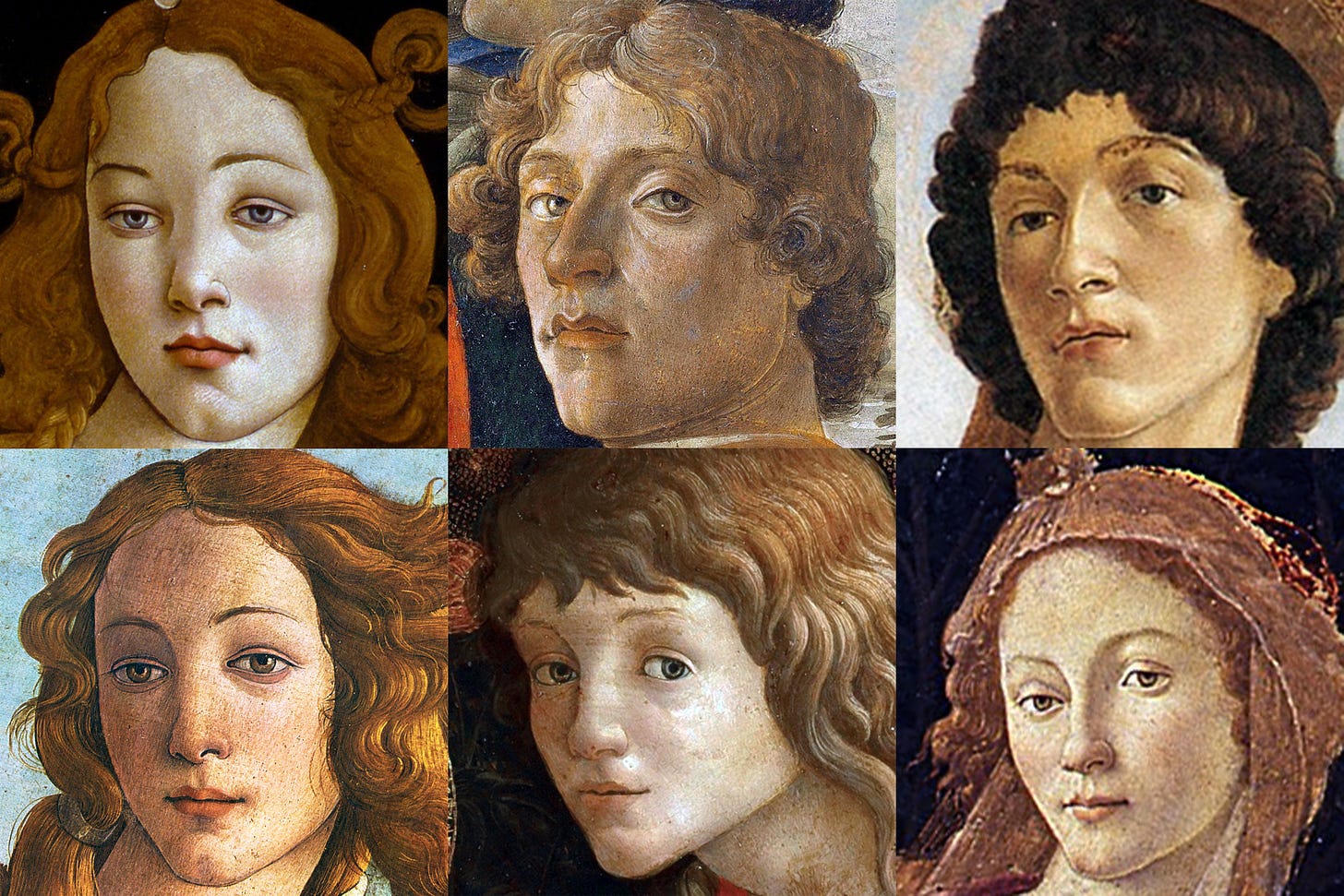

So much for Botticelli himself. The thing is, much the same set of adjectives could be used to describe the faces not just of men, but of also of women and children in his other works. Some examples:

To a striking degree, the adjectives we might use to describe Botticelli can also be applied to these faces. In fact, the St. Sebastian at upper right is so similar to the self-portrait that I suspect this painting is also a direct self-portrait.

The phenomenon is more noticeable when we compare these faces to the painter’s portraits of real people (as opposed to the mythical beings, saints, and angels above):

Even in the portraits, though, a resemblance to the painter shines through:

The “Botticelli-ness” of it all is hard not to notice.

So why does this matter?

One reason I find this topic interesting is because it gets at a fun but rarely noted aspect of historical research: experiential history, or knowledge gained from the real-world practice of the historical profession you’re studying (here’s an example). I don’t paint much anymore, but for a time I wanted to be a professional artist, and I’ve spent thousands of hours in front of easels.

If you’ve painted even one portrait, you soon learn that it’s really hard to get someone to sit still for long. Even if they do, it’s inevitable that the light will change, or they will subtly shift their expression. And all at once, the eyes you spent five hours perfecting look just a tiny bit off.

In those moments, quite understandably, painters tend to reach for a mirror.

In short, perhaps automimesis is just a fancy name for a very practical solution. The painter’s own reflection in a mirror, after all, is the only thing that is available to them for free, whenever it’s needed.

Other times, however, it’s not so simple.

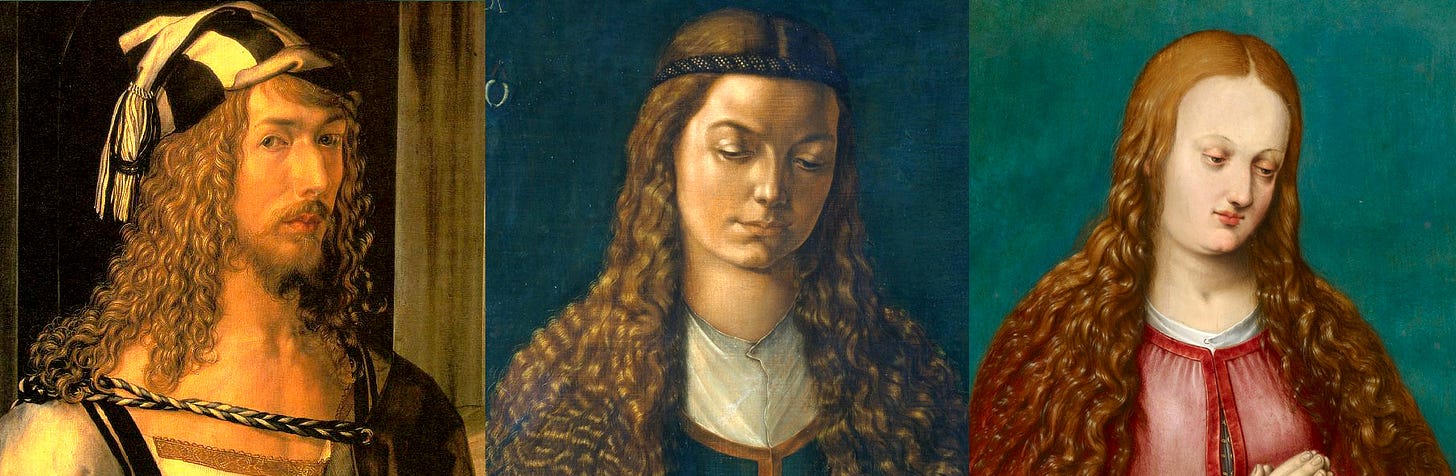

Sometimes it’s not the faces that repeat, but a specific fixation of the artist. For instance, Albrecht Dürer (self-portrait at left) had a thing about hair:

Here’s a more cryptic example, from the work of a remarkable female painter who really ought to be better known. Sofonisba Anguissola (1532-1625) was born to a relatively poor noble family that traced its lineage to a Byzantine general of the 8th century CE. Apprenticed to a painter in the Duchy of Milan, she traveled to Rome as a youth, where Michelangelo praised her talent. One of her portraits then caught the attention of the Queen of Spain, Elizabeth of Valois, an amateur painter herself. Sofonisba became the painting tutor to the Queen and official court painter to King Philip II, of Spanish Armada fame. She died, intriguingly, at age 93 in Sicily.

Here is her self-portrait:

Notice how the Virgin Mary resembles her, right down to the matching hair net. Is she piously mimicking the saintly Mary — or sacrilegiously comparing herself to her?

Another example of “psychological automimesis” comes from the sculptor Benvenuto Cellini (1500-1571). In his shockingly entertaining autobiography, Cellini claims to have helped to summon a demon in the Roman coliseum. He also proudly admits to numerous attempted murders — not to mention firing the arquebus shot that killed the French military leader Charles III, Duke of Bourbon, and ended the Siege of Rome.

Cellini’s nickname — unsurprisingly — was diablo, or devil. According to this article, which was authored by a French expert in “biometry,” a detail in Cellini’s bust of Duke Cosimo de Medici may be a disguised self-portrait playing on this devilish reputation.

Automimesis and the search for immortality

The German art historian Frank Zöllner has argued that artists like Botticelli mirrored themselves in their artworks "involuntarily.” I’m not so sure. Zöllner himself notes that Botticelli was an extreme example of automimesis. Details like this one from Botticelli’s Adoration of the Magi arguably stray into the same uncanny territory as this famous scene from the film Being John Malkovich:

Can this this really be “involuntary”?

Let’s remember how deeply not famous artists were in the late fifteenth century, when automimesis was at its zenith. As with musicians, writers, and actors, early modern artists occupied the fringes of polite society. There were no profiles in newspapers, or monographs by scholars, no galleries or agents or solo shows. Being a Renaissance painter was not so different from being a Renaissance glove maker.

With one important exception: you had the chance to embed yourself in something which you knew — or at least hoped — would be viewable by uncountable thousands… forever.

It’s not hard to imagine that a certain personality type might jump at that opportunity.

An AI-related proposal

While researching this topic, I compared a lot of faces from Renaissance portraits in Photoshop. This got me thinking about the recently-acquired ability of generative AI models to create 3D representations of 2D images. In other words, it’s now possible to rotate faces from artworks in new ways — even to animate them.

The examples of auto mimesis I gave above are all discoverable because we happen to have self-portraits of the artists. But what about the painters who didn’t leave behind a known self-portrait?

Theoretically, it should be possible to create a corpus of all non-portrait faces in a given artists’ known oeuvre, use AI tools to rotate them and even adjust the expression to make them comparable, then create a facial composite. I suspect that this would end up with something reasonably close to the artist’s own face. And it could actually be a useful tool for making arguments about the validity of possible self-portraits, like the ones that da Vinci scholars have long argued over.

Weekly Links

• An intriguingly hyper-specialized blog about the 12th century Muslim inventor and engineer Ismail Al-Jazari and his Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices.

• A nice profile of the brilliant 17th century writer Margaret Cavendish in The Washington Post, who is finally getting her due.

• I also published a piece in the Post on the history and future of psychedelics: “Shifting views about psychedelic drugs require a new category for them.”

Primary source quote of the week

The priest, having arrayed himself in necromancer's robes, began to describe circles on the earth with the finest ceremonies that can be imagined. I must say that he had made us bring precious perfumes and fire, and also drugs of fetid odour. When the preliminaries were completed, he made the entrance into the circle; and taking us by the hand, introduced us one by one inside it. Then he assigned our several functions; to the necromancer, his comrade, he gave the pentacle to hold; the other two of us had to look after the fire and the perfumes; and then he began his incantations. This lasted more than an hour and a half; when several legions appeared, and the Coliseum was all full of devils.

— The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini, chapter 64

What is Res Obscura?

If you received this email, it means you signed up for the Res Obscura newsletter at some point. It is entirely free, and you can unsubscribe at any time.

Why does this newsletter exist? The simple answer is that I love history. I find that a lot of people I meet (and some of my students) don’t share my enthusiasm. I think this is partially because it’s a different experience to learn about the past experimentally — taking wrong turns, getting confused, finding new things — rather than to learn it out of a textbook. I started Res Obscura (“a hidden thing” in Latin) to communicate my passion for this actual experience of doing history. Usually that means getting involved with primary sources themselves, in all their strange glory.

If you liked this post, please consider forwarding it to friends or posting about it on social media. It’s the first since moving to Substack (and becoming a parent in 2022), and I would greatly appreciate the exposure.

Res Obscura is written by me, Benjamin Breen, an associate professor of history at UC Santa Cruz. Thanks to Roya Pakzad for reading this essay.

Speakingn of anthropomorphic research agendas gone horribly wrong in NASA and SETI historical archives:

https://youtube.com/watch?v=p7ruBotHWUs&si=ElTGBK9Ht-7hHw1-

Wonderful essay and comments.

Thank you.

Automimesis and anthropomorphism are inherent aspects of who we are as humans.

Book authors subconsciously (or consciously) engage in automimesis in their writings, and artists subconsciously (or consciously) engage in automimesis in the portraiture they craft.

Jacques- Louis David in his Napoleons, il Parmigianino in his Anthea, and even Leonardo in his La Gioconda, betray automimesis.

I first learned about automimesis many years ago in Simon Abraham’s essays, which he collated at:

Every Painter Paints Himself | EPPH |

Art's Masterpieces Explainer

https://www.everypainterpaintshimself.com/about