Both of our daughters, ages 1 and 3, are home sick with bronchitis, so the post I had planned is delayed until next week.

But I did want to make a small request: if you have any interest at all in supporting Res Obscura financially, this week is a great time to do so. That’s because I have instituted a special Lupercalia discount of 33% off the paid rate for monthly ($4/month) and annual ($40/year) subscriptions.

Subscribe here for the discounted rate:

I’ve written Res Obscura (first as a blog, and now as a newsletter) for fifteen years now. In that period I have written roughly 500,000 words and reached about the same number of readers. None of it has been pay-walled, and I have never accepted any advertising. Your support via these optional paid subscriptions makes a huge difference in allowing me to keep writing. I’m currently at 40 paid subscriptions, and will start sending out special posts for subscribers once I hit 50.

Please help me get there by the end of Lupercalia on the 15th of February (or better yet, by Valentine’s Day):

What is Lupercalia? I wrote about the wolf-themed Roman holiday — and the links further back to the wolf cult of Mount Lykaios in Greece — back in 2011, in one of the earliest Res Obscura posts to get any traction.

Here’s a snippet from it:

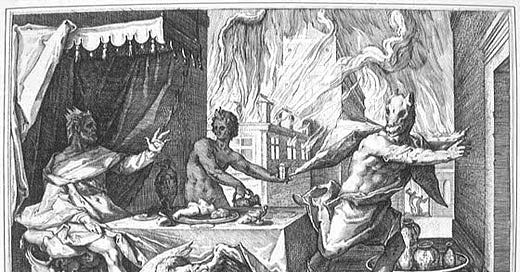

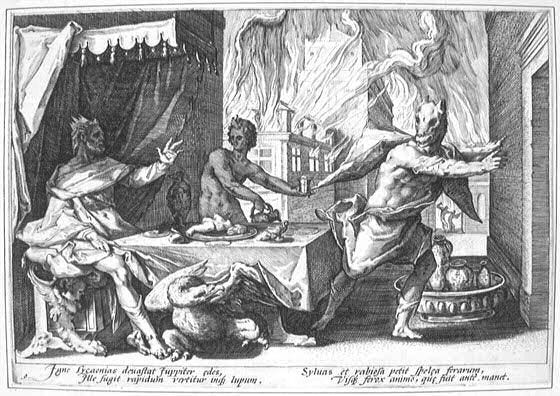

The story begins with the legend of King Lycaon (“The Wolfish One”). According to Ovid's Metamorphoses (translator A.S. Kline), Lycaon was a primitive lord of Arcadia in the earliest era in which humans walked the earth, “when the constellations that had been hidden for a long time in dark fog began to blaze out throughout the whole sky” (I: 68). Yet Lycaon was a king of the Iron Age, when “honour vanished” and “pernicious desires” reigned. His infamous crime was to attempt to trick Zeus into eating the limbs of a dismembered child in order to test his omniscience. But Zeus was not fooled:

“No sooner were these [limbs] placed on the table than I brought the roof down on the household gods, with my avenging flames, those gods worthy of such a master. [Lycaon] himself ran in terror, and reaching the silent fields howled aloud, frustrated of speech. Foaming at the mouth, and greedy as ever for killing, he turned against the sheep, still delighting in blood. His clothes became bristling hair, his arms became legs. He was a wolf, but kept some vestige of his former shape. There were the same grey hairs, the same violent face, the same glittering eyes, the same savage image. [I:210-243]

Several classical authorities linked the wolf-rites of Mount Lykaion to the more famous Roman holiday of Lupercalia. This festival, which spanned February 13-15, was a fertility rite intended to purify and protect the city of Rome. The rite centered around the Lupercal, which was supposedly the very cave in which the she-wolf had suckled Romulus and Remus, mythical founders of Rome.

An Italian archeologist announced in 2007 that the remains of the Lupercal were believed to have been found directly beneath the ruins of the palace of the Emperor Augustus.

The priests of Lupercalia were the Luperci, or "Brothers of the Wolf," who Cicero described as “a wild association... both plainly pastoral and savage, whose rustic alliance was formed before civilization and laws” (Cael. 26). These priests were said to smear blood upon the foreheads of the noble youth of Rome and dress them in shaggy wolfskins. The youths were required to laugh, and seem to have gone into a sort of frenzy. The great historian Plutarch noted the connection with the Arcadian Wolf-Zeus ceremonies and added,

At this time many of the noble youths and of the magistrates run up and down through the city naked, for sport and laughter striking those they meet with shaggy thongs. And many women of rank also purposely get in their way, and like children at school present their hands to be struck, believing that the pregnant will thus be helped in delivery, and the barren to pregnancy. [Life of Caesar, 61]

Thus from 2011. This is now me writing today in February, 2025.

I should note that Lupercalia has no proven connection to Valentine’s Day, and I heartily repudiate the part of the post where I tentatively suggest a link. (I was a little bit more of a freethinker about such things back when I was still in my 20s). I’m a big believer in the long-lasting nature of cultural patterns, not all of which get written up in surviving historical sources, but the multi-century jump from Lupercalia, which ended in Late Antiquity, to the earliest connections of Valentine’s Day with romantic love in the 14th century (for instance, Chaucer’s famous reference in The Parliament of Fowls) is just too much of a stretch.

Interestingly though, the historian Edward Muir, in his book on ritual in early modern Europe, does suggest a link to a Christian holiday. But it’s to the feast of the Purification of the Virgin (Candlemas) earlier in February:

This season connected the pure fertility of the Virgin, who gave birth to the light of the world, to the onset of spring (at least in the Mediterranean) with its promise of the regeneration of nature. Insome ways an amalgam of the Pagan Feast of Lights (February 1) and the Roman Lupercalia (February 15), the Christian purification rituals retained associations with lustration, fire symbolism, and fertility (Muir, Ritual in Early Modern Europe, 68-69)

So happy wolf day to those who celebrate. And a heartfelt thank you to everyone who subscribes to Res Obscura. Thanks!

I was happy to subscribe, and I'm also looking forward to ordering and reading your early modern drug trade history soon! I just finished Debus's classic The Chemical Philosophy and I'm still not tired of the broader subject.

Ben, I appreciate your work here but I'm not sending any money to Substack.

I support writers on Beehiiv, Buttondown, Ghost, Patreon, and elsewhere, because it's important to support the voices you want to hear more of, but right now it's even more important to support the people and organizations pushing back against hate instead of those encouraging and profiting from it.

I look forward to supporting your writing when you move to a different platform.