Role-playing with AI will be a powerful tool for writers and educators

Or, how well can GPT-4 simulate an acid trip in 1963?

The mid-January publication day for my book Tripping on Utopia is fast approaching, and I will have some exciting news to share about book publicity and advance reviews soon. But for now, I am going to return to a topic that has been on my mind over the past year — using generative AI as a kind of history simulator — and try it it out directly on my book’s content.

In fact, I’ve tested it on the content of both my books: the first, The Age of Intoxication, focused on the global trade in drugs, spices, and medicines in the 17th and 18th centuries. Tripping on Utopia is a deep dive into the first era of psychedelic science, focusing particularly on the anthropologist Margaret Mead and the psychedelic researchers of the 1950s.

I’ll describe some highlights below, but if you want to see the complete “transcript” of a simulated experience and setting which was directly inspired by a source I used in Tripping on Utopia, you can find it here:

Why am I so interested in this kind of thing?

It’s understandable that some writers and historians think of generative AI as a competitor. After all, AI-produced books are already showing up on Amazon. It’s only a matter of time before the first AI-generated YouTube series takes off — and the first #1 hit single written and performed entirely by AI, and all the rest. I am not happy at this prospect either. But unlike some, I don’t think that this is the only future path available to us. I’m fascinated by the prospect of generative AI not as a replacement for human authors, but as a tool for allowing us to actively explore and engage with alternative versions of the world.

For instance, the world of a novel that an author is in the process of writing, or the vanished worlds of the past that historians like me spend our time researching and describing.

Educators call this experiential learning. And increasingly, I think various forms of experiential learning will end up being the most lasting and powerful use cases for the current wave of AI systems.

I now have some preliminary data to support what had, before, mostly been a hunch about the potential effectiveness of AI historical simulations. During the fall quarter, I employed versions of the historical simulation activity I described in this previous post in the world history class I have been teaching at UCSC.

I then asked my students to complete an anonymous survey about how these activities impacted their learning. Here is one striking result from that survey:

When given a list to choose from, 71% of the students surveyed said “ability to make choices and decisions as historical actors” was most beneficial to their learning in their class. And fully 84% of the class reported that AI historical simulations “greatly” or “somewhat” enhanced their overall understanding of the time period.

Of course, the paramount problem is that of accuracy: the simulation needs to accurately reflect the historical record in order to be truly effective as a learning tool. I think this problem can be overcome, but it isn’t solved yet. For now, I am making sure to tell my students that the simulations they experience will contain numerous historical inaccuracies. In fact, I make the act of discussing, fact checking, and reflecting on these inaccuracies a key part of the activity itself. Thinking about the unreliability of sources, after all, is a big part of what historians do.

But what about the more solitary domain of creatively imagining another world? When writing Tripping on Utopia, I spent a great deal of time figuring out the chronology of events, fact checking claims, determining the relationships between different people, and other forms of historical analysis that require rigor and factual clarity. But I also spent a lot of my time doing what might best be described as day dreaming. Some of the things on my mind while writing the book:

What’s it like to have a malarial fever?

Would it be too loud to conduct a conversation while sitting in the back of a motorized canoe in 1933?

What are some possible explanations for why Margaret Mead initially volunteered to be a test subject in an LSD trial in 1954, and then pulled out?

What would it feel like to be a volunteer in an early psychedelic experiment?

These are, for lack of a better word, the more “vibes-based” elements of writing history. You can certainly make informed guesses based on the historical record — but you also, necessarily, need to add your own imagination to the task, too.

Generative AI cannot give answers to the questions above. But it can help kickstart the tiny acts of historical imagination and empathy that are so important in writing and teaching history. To get a practical sense of what I mean by this, you can read through this transcript of a simulated acid trip in 1963. The participant, a 32-year-old artist named Leo Mitchell, is fictional, and there are numerous obvious inaccuracies (for instance, his “inventory” includes a tiny bottle of LSD pills — but of course, a volunteer would never have walked into a study of an experimental drug with that drug already in hand!)

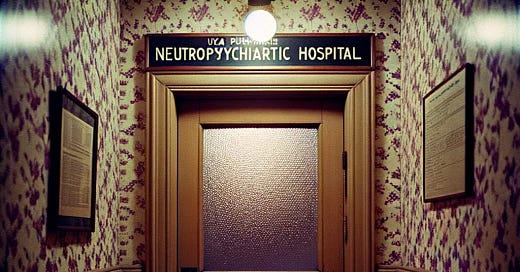

Nevertheless, there's a lot here that I found useful as a historian. For instance, the emphasis on the ambient environment and physical sensations. Leo feels “a flutter of nervous excitement in his stomach” as he enters the Los Angeles Neuropsychiatric Hospital to begin his LSD trial on an October morning in 1963. He notices “the soft hum of the hospital's air system.” As the pill kicks in, “the once calming shadows” dancing on the wall “seem to take on a more menacing quality.”

I found the visual results of the simulation, which were produced by DALLE-3 based on the scenes described, to be similarly evocative. For instance, this one showing Leo staring at his hand in the hallway nicely evoked the clinical backdrop of so many psychedelic studies of the era:

And I was pleasantly surprised by the image below, depicting the moment when Leo Mitchell approaches the offices of Sidney Cohen. It captures Mitchell’s perspective while fully under the effects of the drug, as “the fluorescent lights buzz and flicker, casting strange, moving shadows on the walls.”

The same part of the simulation evokes Mitchell’s inner life in a way I found compelling. Mitchell, an artist, has drawn a charcoal sketch of his own brain and is carrying it in his hand. The simulation notes at this point: “The intricate details of your brain drawing in your hand seem alive, and you feel an immense connection to it, as if it's a roadmap to your current mental state.”

I didn’t have access to generative AI tools like this while writing Tripping on Utopia. But if I had, I would’ve found this experience useful for helping me better imagine the the perspective of a nervous patient experiencing everything for the first time — rather than that of the scientists who produced the vast majority of the primary sources relating to early psychedelic therapy.

Simulating a 1680s doctor

One intriguing aspect of the way generative AI systems are trained is that they contain sedimentary layers of the historical record. It’s not as if everything in their training data was from the last decade, let alone the last century. To cite just one example, large swathes of Wikipedia were copied directly from the 1911 edition of Encyclopedia Britannica, which is in the public domain. This, in turn, means that there’s an awful lot of 1911-vintage knowledge in models like Gemini and GPT-4.

That’s bad for anyone trying to use something like ChatGPT as a search engine to surface reliable facts. But it’s pretty amazing for a historian trying to play around with obsolete and archaic knowledge.

One great example of this idea taken to an extreme is MonadGPT, a language model created by the digital humanist Pierre-Carl Langlais. It’s a version of the open-source Mistral 7B language model that has been fine-tuned on early modern European texts. The result is much as Langlais’ describes: “What would have happened if ChatGPT was invented in the 17th century? MonadGPT is a possible answer.” You can chat with it directly here.

To test how MonadGPT performs when asked to role-play as a physician from the 1680s — one of the key decades I researched in Age of Intoxication — I gave it a randomly-chosen set of symptoms described by the 17th century English physician Thomas Sydenham here. They include “Convulsions,” “a most vehement Pain the Head,” “vomiting up green Matter,” “Palpitation of the Heart,” “Cough” and “the Illiack Passions.”

For Sydenham, these symptoms pointed to only one thing: “the disease called in Women the Hysterical, in Men the Hypochondriacal Passion.”

When I asked MonadGPT to offer a diagnosis and treatment based on those symptoms, the diagnosis it gave was dropsy. It advised that I “eat a moderate diet, and abstain from strong drinks,” and prescribed the following:

Take two drams of Aloes, one dram of Balsam, half a dram of Gum Arabic, and half a dram of Camphire; mix them together in water, and take two spoonfuls every hour. Also take a dram of Rue, a dram of Opium, a dram of Angelica, a dram of Centory, a dram of Poppy-seed, and a dram of Myrrh; mix them together, and take two spoonfuls every day. Take likewise two ounces of Hellebore, and boil them in a quart of water till it be reduced to half its bulk; then strain it through a cloth, and take half a pint of this liquor every day, till the disease be removed.

This was a pretty great recreation of an early modern drug recipe, but it didn’t correctly guess my affliction.

What’s striking, however, is that off-the-shelf, vanilla GPT-4 did — provided I prompted it to “role-play as a doctor from the 1680s.” Here was part of its response to the list of symptoms:

Upon reading thy description of the maladies afflicting this patient, it is my judgment as a physician of the 1680s that we are confronted with a case most complex and multifarious, indicative of a condition known in our times as 'Hysteria' – a disorder primarily attributed to the wandering womb, as postulated by ancient physicians like Hippocrates and Galen… To restore the balance of humors, venesection (bloodletting) may be advised, perhaps by leeches or with a lancet.

However, the language used here was not that historically accurate, and the herbs it went on to prescribe (“valerian and lavender for their calming effects on the mind”) had more in common with modern herbal remedies than with 1680s medicine.

When I made a custom GPT, things improved quite a bit. My “1680s Physician” GPT was provided with a list of common 17th century drug and medicine names (red coral, tragacanth, antimony, laudanum, etc) and given some guidance about the task it should perform (“Treatment recommendations should be strictly within the scope of 17th-century medical practices”).

When given the list of symptoms above, it correctly diagnosed “Hysterick and Hypochondriack Affections” and offered the following treatment plan:

This was not precisely what Sydenham recommended, but it was strikingly close. Sydenham urges: “Let eight Ounces of Blood be taken away.” 1690s Physician GPT recommended “letting no more than eight Ounces of Blood.” Sydenham and the AI both recommended galbanum. In general, the herb and drug remedies prescribed above strike me as in keeping with the sorts of things a 1680s doctor in London or Paris or Lisbon would’ve prescribed.

That’s not to say they directly reflect historical reality, of course. But they allow you to play with the historical record in a novel way — a form of experiential learning which creatively repurposes the source base itself.

For instance, we can’t ask Thomas Sydenham how we would treat Covid-19, but we can ask the 1690s Physician bot (“take of Barley-water, two Pints, Scurvy-grass, one Handful, and Lemon peel, half an Ounce. Boil them together until the liquid is reduced by one half. Let the Patient drink this Decoction warm, at the rate of a Pint each Day”).

What’s it all for?

I keep returning to the theme of historical empathy when I reflect on exercises like this. There are aspects of historical writing and teaching that are stringently objective: did an event happen on a certain date or not, was a person alive or not on that date, were they in x or y location, and the like. Despite overheated claims, I don’t think tools like ChatGPT or Google’s forthcoming Gemini are ready to offer much help to professional researchers when it comes to those challenges. A human historian is still far better than the leading edge of AI systems when it comes to detecting and correcting factual inaccuracies.

But…

… that isn’t what these systems are actually good at. They’re good at hallucinating. As long as you’re clear-eyed about the inherent limitations, those hallucinations can be harnessed as a feature, not a bug.

As AI researcher Andrej Karpathy put it the other day:

I always struggle a bit with I'm asked about the “hallucination problem” in LLMs. Because, in some sense, hallucination is all LLMs do. They are dream machines. We direct their dreams with prompts. The prompts start the dream, and based on the LLM’s hazy recollection of its training documents, most of the time the result goes someplace useful.

For historians and for writers of all stripes, anything that allows you to better connect with your source material on the level of emotion and imagination is useful indeed.

Weekly links

• “In 2006, a Roman oil lamp was scientifically excavated at Jamestown, Virginia, the earliest permanent English settlement in the Americas. This study explores why a 17th-century traveler would bring this ancient lighting vessel to the settlement and how its unusual double depositional history allows us to trace its changing meaning over time.” (American Journal of Archaeology)

• After the Plague: Health and History in Medieval England. The profiles of real people who lived and died in medieval Cambridge here are totally fascinating and well worth checking out.

• The only Byzantine emperor to have visited England (1400 CE). “This emperor and his men always went about dressed uniformly in long robes cut like tabards which were all of one colour, namely white, and disapproved greatly of the fashions and varieties of dress worn by the English, declaring that they signified inconstancy and fickleness of heart. No razor ever touched the heads or beards of his priests.”

If you’d like to support my work, please pre-order my book Tripping on Utopia: Margaret Mead, the Cold War, and the Troubled Birth of Psychedelic Science or share this newsletter with friends you think might be interested.

As always, I welcome comments. Thank you for reading!

I was looking for an example of thinking beyond chatbots for teaching that takes advantage of the weirdness of AI and this appeared in my inbox.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4871171&utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

I was just reading Ethan Mollick et al's AI Agents and Education paper (linked above) and wonder if you have read it too. Because he is at the Wharton School its more about simulation tutoring, mentoring, and other repeated tasks in education than your history simulations, but this is a big area of research at Harvard as well, where a Physics knowledge expert was trained to be a first responder for students who would normally reach out to their TAs. I don't see a publication on this yet but saw a presenation at Stanford by Kelly Miller and Greg Kestin.