Wilfrid Voynich: Bookseller, Revolutionary, Amateur Cryptologist... Suspected Spy?

The first in a series on the extraordinary lives of the Voyniches

To make it clear at the outset: Wilfrid Voynich, namesake of the famous Voynich manuscript, was definitely not a German spy.

This post is about the odd events of 1916 and 1917 that led to his being investigated as such.

I. “He will bear a close watch”

It all began with an unfortunate remark at a dinner party in Chicago.

It was 1916, and Wilfrid Voynich — ethnically Polish, born in Russian Lithuania, a citizen of the UK, and now resident in the United States — was dining with his friend Walter Lichtenstein, the Head Librarian of Northwestern University.

The dinner was both social and professional, for Voynich was a professional dealer in extremely rare books, and Lichtenstein was a man who wielded a large budget for buying precisely what Voynich had for sale. As he often did, Voynich got to speaking about his prized possession: a mysterious codex which he had bought four years earlier in Italy.

Today, it’s known as the Voynich manuscript.

It was a misunderstood remark of Voynich’s about his most famous find that got him tagged by the Bureau of Investigation — predecessor of today’s FBI — as a possible German spy.

This is how a 1917 memo in Voynich’s Bureau of Investigation file puts it:

During the past year we have had in Chicago a man by the name of Wilfred M. Voynich… When he was here last year, he was entertained by the Librarian at his house in Evanston, where there were present two other people, a man and a woman. During the dinner he made the statement that he had in his possession the cipher of the American War Department. This Voynich is the husband of a well-known English author Ethel Lillian Voynich, who wrote the “Gadfly”… He is possibly a German.

In truth, Voynich had recently fled his home in London to avoid World War I (“fearing zeppelins,” as one 1915 newspaper article about Voynich’s treasures put it), and had no connection to German intelligence.

This claim that an antiquarian book dealer “had in his possession the cipher of the American War Department” is likely a result of a bizarre mistake: the Voynich manuscript itself was taken to be a secret American code.

The mixup makes a bit more sense — barely — when we consider another entry in Voynich’s government file. It’s a warning from one W. S. Booth, an otherwise forgotten academic, that Voynich was boasting that he had enlisted the War Department’s codebreakers to try to “transliterate” his “Bacon cipher MS [manuscript].”

Booth passed the letter to the Bureau of Investigation with a note: “I have no reason to suppose that this man is not what he is & and has been known to be — a book seller. But if he has the run of the War Dept. cipher or signals rooms he will bear a close watch.”

The Bureau evidently agreed. A file was opened, and an investigation began.

II. The “Bacon cipher” and the hunt for the Kaiser’s spies

Who really was Wilfrid Voynich?

Almost everything in his Bureau file is wrong. But the truth of Voynich’s shape-shifting life really is deeply mysterious. I find it so surprising that there isn’t a biography of Wilfrid and his wife, Lillian, that I might write one myself.

Reed Johnson’s excellent 2013 article in The New Yorker summarizes the basics:

Much can be written about Wilfrid Voynich. An ethnic Pole from the Russian Empire, Voynich was imprisoned in Siberia for revolutionary activities. He escaped, via Manchuria and China, to London, where he met his future wife, Ethel Boole. Boole, the daughter of the famous mathematician George Boole, who became a popular novelist, was enmeshed in Russian revolutionary activity in London; the bookshop that Voynich set up with her was rumored to be a secret front for organization against the tsarist regime. Whatever the reasons for his entrée into the rare-book business, he apparently took to this work.

See what I mean? Mysterious!

Something I love about Voynich’s story is its fractal-like quality. Each detail seemingly could be expanded into an adventure novel or epic microhistory — if only we knew just a bit more.

For instance, there were several months of trans-Asian travel after his escape from the Siberian prison camp (on his third attempt) before he ended up in Europe. In between, it appears he trekked via caravan from Mongolia to Beijing. He likely had a knack for forging documents, because his escape was achieved by means of a fake passport.

There’s also the fact that his father-in-law was a genius credited with laying the foundation of the Information Age. Or that his wife wrote a best-selling novel that was partially inspired by her torrid affair with Sidney Reilly, the infamous spy who also helped inspire the character of James Bond.

And then there’s his friendship with the Ukrainian nihilist Sergius Stepniak. Wilfrid Voynich and Stepniak co-founded the Society of Friends of Russian Freedom in London. They were both political exiles. Not long before Wilfrid first met him, Stepniak assassinated the head of Russia's secret police on the streets of St. Petersburg with a concealed dagger.

Suffice to say, this is not the typical biography of a rare book dealer.

Perhaps it was some knowledge of this past which made the Bureau take the tip-off seriously enough to arrive on Voynich’s doorstep one day in 1917.

III. The Aeolian Building, 42nd Street, 1917

The Aeolian building is a stately neoclassical skyscraper in midtown Manhattan. It once hosted some of the world’s leading musicians in the grand concert hall on its ground floor. And in 1917, it was also home to Voynich’s Manhattan office.

The Bureau’s agents thoroughly questioned Voynich, then just as thoroughly searched Voynich’s office. They turned up nothing. But that did not end the suspicion. Later that year, agents of Bureau’s civilian auxiliary, the American Protective League, began working the case as well.

The APL officer who led the charge was named Lloyd A. Wimpfheimer. In peacetime, Wimpfheimer worked for a company that sold "hat materials.” In 1917, however, he threw himself with great dedication — and deeply questionable competence — into the role of semi-professional spy-hunter.

Wimpfheimer believed that Voynich was something more than he appeared. Some of his informants seemingly agreed.

The bookseller George E. Smith of 46 East 45th Street, for instance, said he had known Voynich for a long time, “and did not want to do business with him.” Smith “could not give any definite reason, but did not trust him.” (There was likely some professional jealousy at work: Smith took the opportunity to complain that Voynich “was always boasting that he could get manuscripts better than anyone else.”)

Above all, Voynich kept talking up his “Bacon cipher manuscript,” so called due to Voynich’s suspicion (since proven false) that its author was the medieval natural philosopher and monk Roger Bacon.

It is little wonder why Wilfrid Voynich was so fascinated by the riddles of this 240-page text, which is today owned by Yale University’s Beinecke Library. After all, it really is an incredibly strange artifact. There’s no space to describe it here, but Wikipedia does a good job, and you can browse full scans at Wikimedia Commons.

Ultimately, the APS agents learned enough about Voynich and his obsessive quest to decode the manuscript to realize that they were on the trail of a very, very cold case.

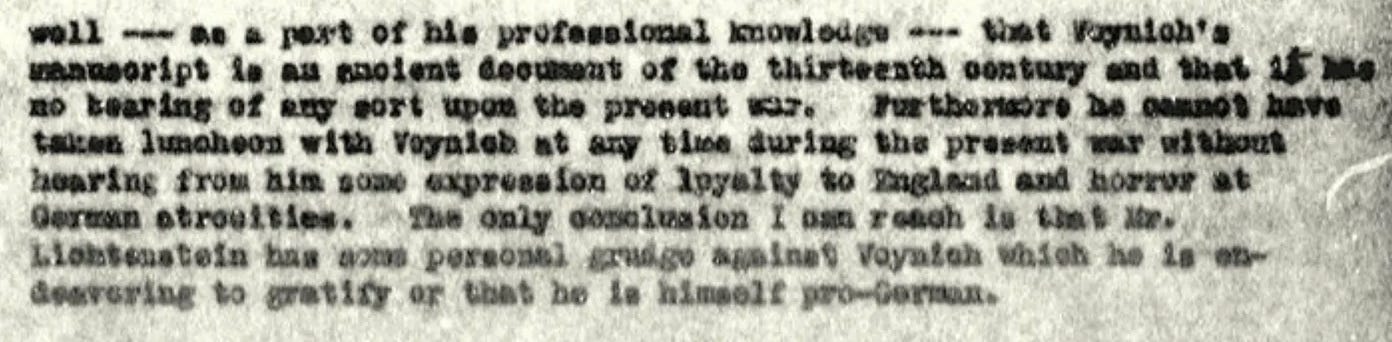

They reluctantly concluded that, as one of informant put it, this was “an ancient document of the thirteenth century” with “no bearing of any sort upon the present war.”

IV. The takeaway?

An incredible amount of intellectual energy has been, and is still being devoted to the Voynich manuscript. Personally, I suspect that it may never be decodable (I’m agnostic about its origins, though I think that the theory that it’s an instance of graphomania is underrated).

But even if manuscript itself is unknowable, might there be value in the hunt?

In the end, Voynich’s efforts to interest the codebreakers of the U.S. military in his codex were actually taken very seriously. There is a whole branch of Voynich research spearheaded by major figures in the National Security Administration. One notable Voynich enthusiast, for instance, was the NSA’s chief cryptologist William F. Friedman, who, with his wife Elizabeth, made some of the twentieth century’s most notable contributions to crypytology.

Perhaps Voynich’s manuscript was just a hobby for these figures. But then again, perhaps they found something practically useful there, too.

After all, there was a precedent. The Friedmans became involved in codebreaking thanks to disproven (but extremely persistent) theory about the authorship of a different set of early modern texts: the works of Shakespeare.

Here’s how a review of an exhibit on ciphers at the Folger Shakespeare Library puts it, quoting the early modernist Bill Sherman (whose book on John Dee, by the way, is great):

The lynchpin of the new exhibit is William Friedman, whose unlikely career links Shakespeare scholarship to Cold War cryptography. Friedman and his wife got their start in the early 20th century working for an eccentric millionaire who was determined to prove that Francis Bacon was the secret author of the Bard’s plays.

That futile project failed, but in the process, Friedman became an expert in codes and ciphers. When World War I began, the U.S. military realized he had the skills they needed. He remained in the field for decades, and he and his colleagues eventually broke Japan’s Purple cipher during the war.

“Without this crazy argument about Bacon writing Shakespeare’s plays,” Sherman says, “we might not have won the war in the Pacific!” [Source: Ron Charles, “TOP SECRET: From Shakespeare to the NSA,” The Washington Post, Nov. 10, 2014]

This is the first post in a series. Next time: Ethel Lillian Voynich, née Boole.

Further reading in Voynich’s file and an erudite explanation of the contents can be found on Colin MacKinnon’s fascinating website, along with a host of other Voynichiana. On the history of the Bureau of Investigation, see Beverley Gage’s wonderful book G-Man.

Weekly Links:

• The cipher on William Friedman’s tombstone (designed by Elizabeth after his death in 1969) was solved in 2017.

• “A Partial Decipherment of the Unknown Kushan Script” (“šaonano šae ooē // mo ta k // t oe, ‘This [is the …] of the king of kings, Vema Takhtu”)

• "Jarry died in Paris on 1 November 1907 of tuberculosis, aggravated by drug and alcohol misuse. When he could not afford alcohol, he drank ether. It is recorded that his last request was for a toothpick.” (Wikipedia)

• “Detail from a handwoven manuscript textile depicting the popular chicken-and-ancestor motif” (British Library).

Primary source quote of the week

"The writers of natural magic report, that the heart of an ape, worn near the heart, comforteth the heart, and increaseth audacity. It is true that the ape is a merry and bold beast. And that the same heart likewise of an ape, applied to the neck or head, helpeth the wit… It may be the heart of a man would do more."

— Francis Bacon, Sylva Sylvarum, or, a Natural History (published posthumously in 1627)

What is Res Obscura?

If you received this email, it means you signed up for the Res Obscura newsletter, written by me, Benjamin Breen. It is free, and you can unsubscribe at any time. I started Res Obscura (“a hidden thing” in Latin) to communicate my passion for the actual experience of doing history. Usually that means getting involved with primary sources, in all their strange glory.

If you liked this post, please consider forwarding it to friends. Another way to support my work is by pre-ordering my book Tripping on Utopia, which will be published in January 2024.