LLM-based educational games will be a big deal

For the first time, digital games can make qualitative assessments of learning. Here's what that might look like.

![[optimize output image] [optimize output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!kiQq!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F602f828d-d4e5-48d5-a3cb-77c47a783dc5_1892x1319.gif)

For more than a year now, I’ve been experimenting with using ChatGPT (and more recently, Claude and Gemini) to create deeply imperfect — but also, I think, fascinatingly weird and pedagogically useful — “simulations” of historical settings for use in my classes at UC Santa Cruz. The initial simulations were crude proofs of concept, but I have since developed them into a larger set of activities and assignments that I call “HistoryLens.”

The basic idea goes like this:

The instructor creates a “prompt” which integrates a standard set of rules with a specific setting, event, and/or historical source tailored to the course content.

Working in pairs or alone, students paste this prompt into ChatGPT or an LLM of their choice, then decide how to act within the text-based, interactive scenario it creates based on the specified setting, date, and sources.

Group and class discussions, plus a series of follow-up assignments involving fact checking the simulation and researching questions it raised, allow students to integrate, critique, and reflect on the experience — while also gaining sustained experience with a complex use case of generative AI.

You can read about my early experiments with this setup here:

Recently, I’ve been thinking about what the next steps would look like. Could this sort of thing be the early stage of a whole new category of educational games that will impact how we teach and learn?

I think the answer to that question is “yes.”

Educational games have been around for a long time, but I believe that the advent of generative AI really does mark something new here. There are two key assumptions I’m making that explain why I’m so excited about the possibilities.

Proposal 1: In the near term, education may be the most important field for generative AI

Using anything as error-prone as the current generation of consumer-facing LLMs in life-or-death applications like healthcare is downright terrifying. Tools like ChatGPT are simply too prone to hallucinations and prompt injection to be acceptable in situations where truly impactful decisions are being made.

But what about in the classroom, where the stakes are lower and confusion can be productive? Discussions of LLMs in education so far have tended to fixate on students using ChatGPT to cheat on assignments. Yet in my own experience, I’ve found them to be amazingly fertile tools for self-directed learning. GPT-4 has helped me learn colloquial expressions in Farsi, write basic Python scripts, game out possible questions for oral history interviews, translate and summarize historical sources, and develop dozens of different personae for my world history students to use for an in-class activity where they role-played as ancient Roman townsfolk.

And although all this might sound somewhat niche, keep in mind that there are thousands of classrooms where this sort of thing is happening. Education is a huge and impactful field, one that accounts for 6% of the total GDP of the United States and which represents one of the largest employment sectors globally.

Given this, I find it somewhat surprising that media attention so often focuses on the hypothetical uses of AI systems. Sure, future LLMs might develop novel cancer-fighting drugs or automate away millions of jobs. But that’s by no means assured. What is definitely assured is that generative AI has already become interwoven with secondary and postsecondary education. According to one study, over 50% of American university students are using LLMs. That percentage will likely continue growing fast — especially given the rollout, just yesterday, of OpenAI’s free “GPT-4o” model, which is a major advance over the previous free LLMs that were available.

In other words, now is the time to find uses for LLMs as tools for learning rather than cheating. That means exploring the new modalities they open up.

For example…

Proposal 2: Educational games are a major real-world use case for LLMs

I already wrote about why I think LLMs are such interesting tools for educational role-playing, so I won’t rehash the argument here. But what would that look like in practice? So far, my classroom experiments with HistoryLens have been mostly about figuring out whether the basic concept of AI-enabled historical simulations even makes sense. Are the AI models capable of pulling it off? Do students like it? Does it augment their understanding of course material, or detract from it?

Since these are still largely unanswered questions, I have been focusing on the basics so far. But what would it look like if we were to develop fully-realized LLM-enabled educational games?

The ideas

Below, I describe three ideas for games which I can imagine deploying as an integral part of a course. For instance, Young Darwin below would fit into a class I sometimes teach at UCSC called “Tropics of Empire,” about the tropical belt, imperialism, and the Scientific Revolution.

You can click here to access a Google Doc with prompts corresponding to each idea. Enter the prompt into an LLM of your choice (Claude, Gemini and ChatGPT all work) to experience it for yourself. But keep in mind that this is just a proof of concept: in each case, the actual game I am imagining would include a graphical user interface and additional features like the ability to save or to toggle historically authentic languages.

Idea #1: 🐢 YOUNG DARWIN

Set on the Galapagos Islands, this simulation drops players into the dusty boots of a young Charles Darwin. Players explore various habitats, represented by a grid of emojis depicting flora and fauna, to collect and catalog natural specimens. The gameplay also involves managing Darwin’s thirst and fatigue and encountering occasional random events which upset Darwin’s plans. Players write journal entries to describe their findings.

Victory conditions: Gather ten specimens and write sufficiently high quality journal entries about them before being forced by injury, mishap, or events to return to the HMS Beagle.

This idea was a natural outgrowth of the ability of current LLMs to create crude maps using labelled emojis. I had originally written a prompt to simulate a young Charles Darwin wondering around Chatham Island, where he first observed his famous finches and the Galapagos tortoise. I tried asking the AI to “create a map showing the various lifeforms Darwin is able to discern at this moment using a grid of emojis, in the style of the old game SimLife” and was charmed by the results (see the screenshot later in this post for an example).

This idea would develop that prompt into a standalone game where Darwin moves over a simplified, grid-like map of Chatham Island that is populated by a changing array of life forms (the actual species that the historical Darwin wrote about). The player would observe these species. But crucially, it doesn’t end there. The player would then write journal entries which draw upon original research into actual historical sources, like Darwin’s journals and the works of other naturalists who influenced him. You “win” by writing entries that accurately reflect the mindset and theories of 1830s scientists. More on how that might work below.

Idea #2: 🌿 MEXICO CITY APOTHECARY

You are Maria de Lima, a female apothecary in seventeenth-century Mexico City. The gameplay is centered around mixing medicines according to Galenic techniques to treat patients with various ailments. Players select from a list of historical drugs and prepare remedies, with a GPT model assessing the historical accuracy and effectiveness of their remedies. The challenge lies in managing the shop’s reputation, avoiding public revelation of Maria’s past, and maintaining financial stability.

Victory conditions: Players win after surviving 20 turns without being apprehended by the Inquisition, losing their license due to poor patient outcomes, or running out of funds.

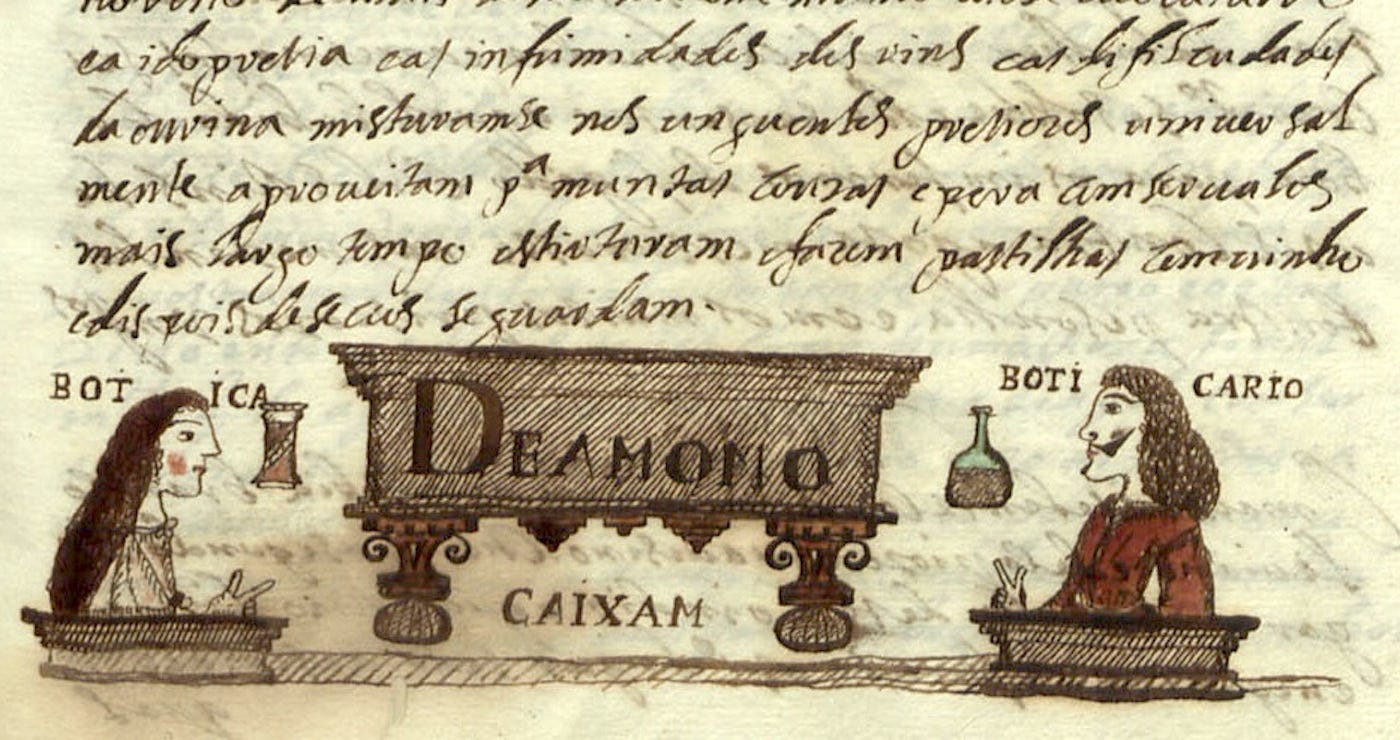

This idea is an outgrowth of my first book on the early modern drug trade, which relied a lot on the archival records of 17th century apothecaries. In particular, I’m interested in using a real, but little-known, historical person as inspiration here: Maria Coelho, a Portuguese apothecary who was prosecuted by the Inquisition for heresy in the 1660s (she was a converso who was accused of secretly practicing Judaism) and deported to Brazil. This is an image from a manuscript that I used in my book research, and which may depict either Maria or a relative at left:

What if Maria forged a new identity in the New World, and ended up in Mexico City running a new apothecary shop? What if this game could actually utilize the prices and lists of medicines available in real 17th century manuscripts like the one above?

Idea #3: 🕵🏼 Cybernetic Spies

Against the backdrop of the 1946 Macy cybernetics conference in post-WWII New York City, choose to play as either anthropologist Margaret Mead or a fictionalized OSS agent turned potential Soviet spy who is based on the real-life story of Jane Foster Zlatovski. Players converse with other conference attendees and make strategic choices that affect their objectives. Margaret Mead aims to develop groundbreaking insights into machine intelligence, while the character based on Jane Foster must choose between espionage for the Soviet Union or blowing the whistle on the presence of Soviet spies in New York. The game takes place over one full day of the conference, with events and dialogue based directly on real events.

I plan to write a subsequent post as a detailed case study of how a game like this might work, so I won’t go into more detail about it here. I had a lot of fun making mockups of this one (mostly a matter of altering and arranging pixel art made by the DALL-E image generation model).

In all three cases, I envision the game itself as being quite barebones in terms of graphics. Papers, Please is a good model for the UI and game mechanics, which would be based on static images of characters with fixed attributes, but with dialogue and interactive events that would be written by an LLM. But really the closest analog to a game of this type — since it relies on students’ doing original research into the topic, then dynamically deploying it — is something more like Model UN or the Reacting to the Past system, a set of educational role-playing scenarios and lesson plans.

Winning a game by writing a theory

My goal with these concepts is to make historical thinking and writing into the central gameplay mechanic. This is something that was impossible before LLMs. That’s because historical learning is not about memorizing facts, but instead assessing, critiquing, and recombining new and existing data. A game can relatively easily check if the player has scored x number of points or selected the correct answer from a group of multiple choice questions. But no matter how complex its rules, older video and board games could never hope to judge whether a player had written something that was historically accurate or rhetorically sophisticated.

For example, let’s look at one of the several Darwin-themed board games in existence. The newest and most popular is called Darwin’s Journey. As the game description puts it, “each worker will have to study the disciplines that are a prerequisite to perform several actions in the game, such as exploration, correspondence, and discovering specimens in order to contribute to the human knowledge of biology.”

But this does not mean that you win the game by actually studying or deploying knowledge. Instead, the educational aspect is represented via a set of identical “knowledge” and “research tokens.”

Now, though, it actually seems to be possible to create a Darwin game in which winning requires the player to do original research into Darwin’s writings and then deploy what they learned in the form of written text.

For instance, an LLM might receive input like this:

You are assessing player input for a text-based educational game called “Young Darwin.” The player assumes the role of Darwin as he wanders Chatham Island hunting for naturalia. Players score points (0-10 scale) based on their ability to observe, write, and theorize about individual species they encounter by writing about them in a series of journal entries. Key assessment criteria is how accurately the player’s journal entry reflects 1830s-era knowledge and modes of thought about the natural world. The player is allowed to conduct independent research into Darwin’s actual journals and writings. Please assess the following journal entry on this basis, assigning it a score between 0 (lowest score) and 10 (highest). Explain your score in two pithy sentences, including concrete and specific critiques and/or corrections. [student’s journal entry follows]

This would then result in a numerical score between 0 and 10 and a fairly detailed explanation, and those points could be tallied up to determine whether and when a player “wins.”

I’ve written this up as a hypothetical, but there’s the thing. Current AI systems can already do this.

For instance, in the prototype version of Young Darwin for use with ChatGPT that I linked to above, I identified a finch near me. It’s the 🐦 symbol on the map here:

I walked toward it, then asked for and was supplied with a detailed description. I then wrote a journal entry after reviewing the LLM’s output and doing my own research into Darwin’s actual account of the finches of Galapagos — which, despite being famous, turns out to amount to only a few sentences.

Here’s what I wrote, trying to assume the voice and knowledge base of young Darwin:

September 17, 1835. Alighted earlier this morning on Chatham Island, most easterly of the Galapagos Group. It is a most bare and craggy expanse of volcanic basalt interspersed with rock and sand, broken up here or there by the occasional cactus or scrubby bit of brush. The climate is arid and hot. I have now observed a most curious species of ground finch which I wish to make note of. These finches are small and rather unobtrusive, but in this landscape they stand out quite distinctly. I believe I have never before observed this particular species. Plumage is quite dark. It is roughly the size of a sparrow, a rather energetic bird which repeatedly chirps. I would reckon each call to last approximately three seconds. I cannot yet determine if this specimen is male or female, but the dullish black-brown coloring would suggest a female. The most striking characteristic of this bird is the robust beak, which is manifestly useful for breaking the small seeds which I observed nearby the bird, and which indeed it was engaged in eating and breaking as I came upon it. I recall no other finch in my experience, or in my reading in Buffon, Humboldt, or others, which bears so large a beak relative to its body size.

And here’s how GPT-4 scored and assessed my journal entry:

Score: 8/10 Explanation: This journal entry demonstrates a strong grasp of observational detail and aligns well with the scientific inquiry style of the 1830s. The mention of notable naturalists like Buffon and Humboldt situates it firmly within the intellectual context of Darwin's time. The description of the finch’s behavior and physical characteristics, particularly the robust beak, is aptly noted and reflects the focus on morphological features typical of 19th-century natural history. However, there are minor points for improvement: • The assumption about gender based on plumage color could use clarification, as such distinctions were not well-understood in Darwin's time and might reflect a more modern interpretation of sexual dimorphism in birds. • The entry could benefit from a more explicit connection between the observed traits and their potential adaptive significance, a key aspect of Darwin's developing thoughts on natural selection, although he had not yet fully formulated this theory by 1835.

This ability for a machine to assess and score text is usually discussed in the context of grading student work. I don’t want current AI tools to be directly involved in grading papers, and I am definitely not alone in that. But when it comes to assessing complex input into an educational game, I think this is a remarkable new capability that should be embraced and explored.

The affordances of video games have always been reducible to number-crunching. Behind every event in a game, there was a formula that decided whether you succeeded or failed. That basic fact greatly limited the kinds of input you could provide a game world with. Did you push a button in time to make the jump or land the hit? Did you move the cursor to the right x and y coordinates? Such were the questions that video games have always hinged on.

Now, though, we have an entirely new set of criteria to judge success or failure in a game world. Because LLMs are able to simulate subjective critique of a piece of writing (or speech, or visual art), this means that the victory conditions for future games can expand beyond the realm of math and into that of words. It is now possible to imagine winning a game by making a convincing speech, or even by painting a beautiful picture. Current discussions about the role of LLMs in gaming have tended to focus on their potential role in generating dialogue for NPCs and the like. But for educational games, I find the new possibilities opened up on the assessment side to be even more interesting.

There’s much more to say about this topic But I will stop here and pick it up in a future post. If you are interested in collaborating on any aspect of the above, please get in touch.

Weekly links

• “Player-Driven Emergence in LLM-Driven Game Narrative”: a new paper from Microsoft Research studies the choices made by players of a 1980s-style text-based mystery game that has been hooked up to an LLM (GPT-4). Their key finding: “given the opportunity presented by a non-deterministic LLM, human players are able to collaborate with the model to introduce interesting, unpredicted new paths through the game narrative in ways that would not be possible with pre-scripted experiences.”

• The Climate Archive: An interactive visualization of climate model data across time and space.

• “Laudatio Turiae (‘In praise of Turia’) is a tombstone engraved with a carved epitaph that is a husband's eulogy of his wife... The stone itself is broken, and parts have been found scattered around the city of Rome, although some sections remain lost.” (Wikipedia)

If you received this email, it means you signed up for the Res Obscura newsletter, written by me, Benjamin Breen. I started Res Obscura (“a hidden thing” in Latin) to communicate my passion for the actual experience of doing history.

If you liked this post, please consider forwarding it to friends. I’d also love to hear from you in the comments.

I was absolutely captivated by this issue. Honestly, using GenAI to create classroom simulations is something that gives me a strong sense of excitement and fascinates me greatly. Especially, when there are best practices like this to inspire me.

In particular, I think they can be increasingly used in more varied contexts and subjects. For example, let's imagine the case of an organizational crisis after some students have learned crisis management concepts.

It's really interesting and the professor's guidance could reduce any friction or reduce some problems. And I think that we can also fuel a reverse process, where these capabilities

simulations will be used more and more to diversify themselves (with a great eye on the part of the videogame industry). Thanks for sharing this!

Very cool, Benjamin. I agree that for better or worse, education will become an increasingly central target for generative AI, especially as regulation begins to emerge in other domains like medical applications. Your gaming angle here is a good example of how we can experiment with these tools to help students to engage more deeply with the course content.

Curious if you've seen anyone compile a set of best practices or guidelines for integrating AI into pedagogy in this way? Seems like there might be some interesting questions to ask and some valuable pedagogical research to carry out.