Margaret Mead, Technocracy, and the origins of AI's ideological divide

The anthropologist helped popularize both techno-optimism and the concept of existential risk

I.

This week may end up being remembered as an inflection point for the social history of AI. I say social history because the underlying technologies likely won’t change much. What will change — I suspect — is the role that AI tools and AI researchers play in our culture.

That’s because OpenAI’s recent fracturing has brought a larger ideological divide into public view.

As Karen Hao and Charlie Warzel write in a recent Atlantic article:

[Sam] Altman’s dismissal by OpenAI’s board on Friday was the culmination of a power struggle between the company’s two ideological extremes—one group born from Silicon Valley techno optimism… the other steeped in fears that AI represents an existential risk to humanity and must be controlled with extreme caution.

Part of why I’ve been so fascinated by the drama at OpenAI is that I’ve spent the past five years researching and writing a book that’s partly about how these two ideologies emerged.

That book, Tripping on Utopia, centers on the early history of psychedelic science. But the book is also about something bigger: the rise and fall of technological utopianism in the twentieth century, as told through the doomed romance between the anthropologist Margaret Mead and her third husband, Gregory Bateson.

Though Mead was globally famous in her lifetime, I think her historical impact is substantially underrated today. A pioneer not just in anthropology but also in science communication (a teenage Carl Sagan was one of her many fans) Mead was probably the most ambitious and controversial American scientist of her generation.

She was also, for a time, a leading proponent of what is now often called techno-optimism: the belief that technology will propel our species toward a transcendent new state by expanding human potential. Mead thought those changes were impossible to predict with any certainty. She just knew they were coming, and that she wanted to be part of them.

If humanity was to survive the twentieth century, Mead wrote in July of 1939, we needed “to envisage a world in which new social inventions will permit us to draw upon human potentialities as never before... to build a world which shall be as new in the ordered interplay given to man’s myriad gifts as the present world is new in the technological utilization of physical resources.” The alternative, she wrote, was “a frightened retreat to some single standard which will waste nine-tenths of the potentialities of the human race in order that we may have a too dearly purchased security.”

Part of why Mead is so intriguing is not just that she was saying this kind of thing back in the 1930s. It’s that, after World War II, she also became a prominent theorist of existential risk.

In other words: the same person helped inspire the two supposedly opposed schools of thought that are battling it out in AI research today.

After the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Mead and Bateson dedicated themselves to publicizing the existential threat posed by the atomic bomb. In speeches, articles, and radio appearances, they argued that the creation of a world government was the only path which could ensure humanity’s survival. Bateson, who was deeply troubled by his wartime experiences in the OSS, the predecessor organization to the CIA, was markedly more pessimistic than Mead about our collective odds. Once, in 1947, Bateson spent the night at J. Robert Oppenheimer’s house. Over breakfast with the physicist’s family, the two men discussed whether “the world is moving in the direction of hell.” They both agreed it was.

What makes Margaret Mead such a complex figure in the history of twentieth-century science is also what makes her relevant for understanding AI in the 2020s. She sought a middle way between the dystopias conjured by Bateson and the naive assumptions of the earliest techno-optimists (more on that below).

In the end, I don’t think she was successful. Tripping on Utopia’s title is not just a reference to the psychedelic experience, but an assessment of Mead’s scientific legacy. Throughout her life, she was driven by a burning ambition to create a better world — and, again and again, this ambition led her to overlook the ethical failings of people close to her. Her life was a case study of the dangers of longtermism.

On the other hand, I can’t help but admire her idealism — or appreciate her timeliness. Flawed as it was, her effort to construct a path toward human flourishing amid the hatred, nationalism, and violence of the twentieth century is all too relevant today.

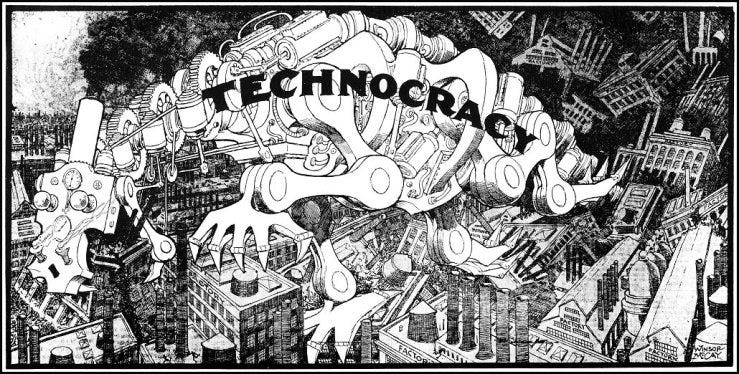

Below is an excerpt from Tripping on Utopia. For reasons of space, I ended up cutting it from the final draft of the book. It’s about a young Margaret Mead’s friendship with Howard Scott, the founder of the Technocracy movement, and the ways that technological utopianism manifested in the culture of the 1930s and 1940s United States. It’s been much on my mind as I read the news today.

II.

Howard Scott and Margaret Mead were similar, and they knew it. She remembered him in her autobiography Blackberry Winter as “an extraordinary person... endlessly inventive and prophetic” who “made a great contribution… to my thinking.”

They shared the same galvanizing power of conjuring new futures. And they shared the same failings. If Mead was a genius, her genius manifested in her ability to push groups of people toward some larger goal which they found, to their surprise, that they were now able to achieve. “Margaret seemed to live in a field of force that could combat anything nature had to offer,” Robert Jay Lifton recalled.1 Sometimes, though, her “self-critical faculties would desert her” and she would spin out into extravagant speculation. Mead’s flirtation with Scott’s Technocracy movement was one such example.

A so-called “mystery man” with “Utopian dreams” and a penchant for double-breasted suits, Scott was like an Ayn Rand character come to life. His mysterious origin story provided much of his appeal. According to one article, Scott surfaced in 1920s Manhattan as a furniture wax salesman and unconventional engineer, “one of the many loquacious habitues of the candle-lit gathering places of New York’s Bohemia—Greenwich Village.”2 As the Great Depression began, Scott emerged as the leader of a movement which claimed that engineers could leverage technological automation to eradicate poverty.

A wire article from the end of 1932 offers one of the clearest summaries of Scott’s ideas around the time of his friendship with Margaret Mead. Technocracy, it said, called for “a nation eventually to be controlled by engineers.” The goal: automating industry so that the average person would need to work only a dozen or so hours a week.

“Nobody can bring this about but engineers,” Scott was quoted as saying. “So far they have been very successful in doing away with material waste and duplication of energy in the various industries in which they are employed. But they have not thought of American industry as an industry in itself. The time has come when that must be done. We are nearing a crisis.”

Soon, however, the cracks began to show. Despite his outlandish goal of leading the creation of a continent-spanning “Technate,” Scott seemed never to have traveled beyond the eastern half of the United States. More damagingly, he had no professional training as an engineer.

Mead recalled in her memoirs:

At the height of his notoriety, Howard was attacked as an impostor who made all sorts of false claims about his activities and his training. In fact, he had only completed the ninth grade, but his prevision of the electronic revolution was extraordinary. His lack of mastery of the intermediate steps was one of his great handicaps and perhaps also the very vividness of his accounts of people he had never met, places he had never seen, and dams he had not built… Had his education matched the scope of his imagination, would he, I have often wondered, have had a profound effect on the country, or was he a forerunner, a man born before his time?

The rise of the New Deal, which included figures once involved in Technocracy, took the wind out of Scott’s sails. After the death of the woman who had introduced them — Scott’s longtime mistress and Mead’s close friend, Eleanor Steele — Mead distanced herself from his movement. But she still carried elements of his techno-utopian ethos into her later work.

One difference was that Mead thought both bigger and smaller. Scott spoke of vast hydrology projects in which the individual human was invisible. Mead saw nothing but the human. And she spoke not just to American intellectuals but to the people of the world. True, like Scott, she argued that scientists should work actively to create a new global society. But this project could never be achieved by scientists or engineers alone. Every human culture, Mead wrote, “bears witness to some different potentiality of the human spirit, to some special source of life untapped by other cultural forms.”

In other words, the global refashioning of humanity’s destiny would have to be just that: global. It could never succeed if it was led by a single culture, let alone a single group within that culture… for instance, a cult-like sect of American engineers.

III.

Though the original Technocracy Movement became a footnote in the history of the interwar years, the term it popularized has proven to be surprisingly resilient.

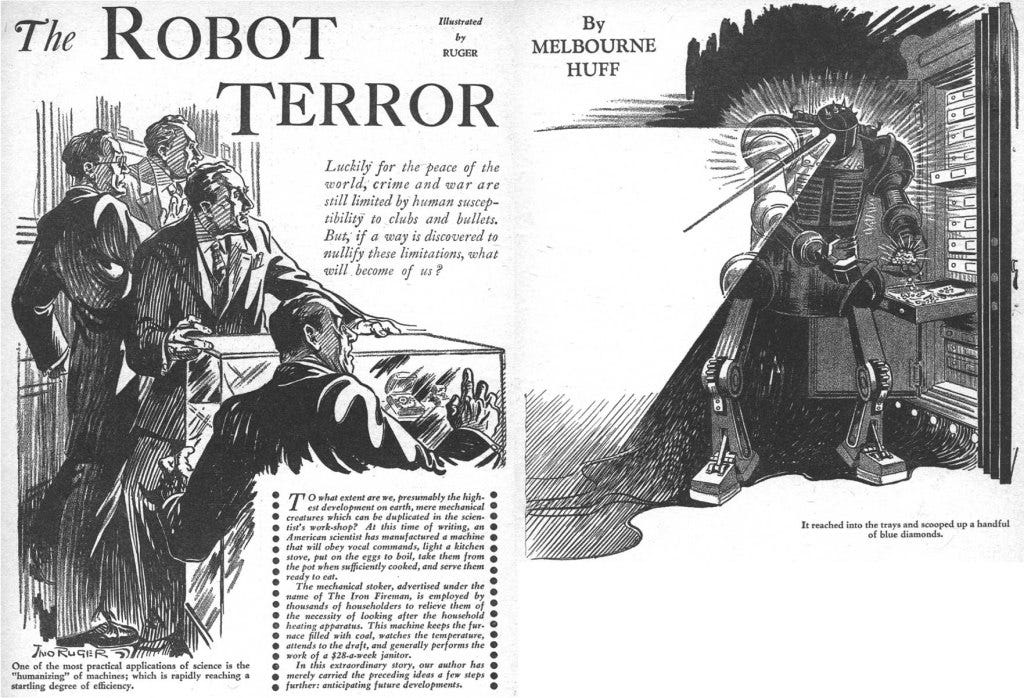

And it was not just the term “technocrat” itself that survived. The techno-optimism of the 1930s persisted in mass media, especially in the science fiction magazines of early “pulp” publishers like Hugo Gersback.

Technocracy Review, Gernsback’s short-lived attempt to cash in on the movement’s 1930s heyday, didn’t last long. But the science fiction magazine format Gernsback pioneered did.

A search of the pages of Astounding Science Fiction (the magazine that replaced Gernsback’s offerings as the leading sci-fi periodical of the postwar period) reveals the extent to which both techno-optimism and fears of “AI apocalypse” already pervaded pop culture by the 1940s. Though these publications were niche, they were influential. Astounding was so widely read by the engineers of the Manhattan Project that its editor, John Campbell, claimed to have been able to guess the existence of a secret research center at Los Alamos, New Mexico simply by noting how many of his subscribers had moved there.

Margaret Mead was close with many in that group — she counted John von Neumann as a friend, for instance. And if anything, she was even more important in popularizing both the concepts of existential risk and techno-optimism. What sets her treatment of these ideas apart is the degree to which she attempted to turn them into a global project of mass culture.

In his epic history of the nineteenth century, The Transformation of the World, German historian Jürgen Osterhammel argues that the period between 1870 and 1930 was unprecedented in part because “the scale of human mobility sharply increased.” Steamships and railroads, colonial empires and missionaries, telegraphs and telephones began to create modern globalization as we know it. But, Osterhammel notes, although “knowledge of the non-European world increased appreciably in the west” (thanks in part to the first generation of anthropologists and ethnologists) “it yielded no practical consequences.” As late as the 1920s, he argues, “whereas the East borrowed all it could from the West — from legal systems to architecture — no one in Europe or North America thought that Asia or Africa offered a model in anything.”3

The key difference between Mead and the proto-techno-optimists of the Technocracy movement was this: Margaret Mead believed the model for a future culture had to be global. It could not be imposed by Western colonial powers (which she opposed) or by scientists alone. It could not be a synthetic culture cooked up in a research lab. Instead, it had to be an interweaving of thousands of different cultural patterns: a truly collective project.

In this, I think she was right. It’s still unclear if the current AI boom really will lead to an Industrial Revolution-level alteration in global society. And even if that transformation does come to pass, it’s even less clear that it will be, on net, a good thing for the majority of the world’s people. But if events do break in that direction, I hope it’s Mead’s skeptical, humane, and cosmopolitan version of the techno-optimist path that wins out.

Weekly links

• Much current writing about artificial intelligence blends together into one of two boring soups: either grifters promising the world alongside 🤯 emojis, or knee-jerk skepticism presented as sage wisdom.

’s newsletter never does. I liked this from the most recent issue: “it is as if the world is filling up with ghosts of its own past who are summoned from silicon substrates to predict its own future.”• Also check out

’s for uniquely well-informed takes on using AI in teaching and research.• A third Substack I love which covers entirely different terrain:

from writer Brandon Taylor. And there’s also the wonderful by . In general, the range of interesting stuff being posted on Substack right now makes me feel like I made the right choice moving here earlier this year. The diversity of perspectives and serendipitous approach to discoverability reminds me of the good parts of the early Internet.• Kalasmaic, a newly-discovered language that was recorded in the Hittite empire. From the Wikipedia page for Kalašma, the Bronze Age state in which it was spoken: “The location of Kalašma is uncertain; scholars infer it from references in contemporary documents to nearby places, many of whose locations are also uncertain… Harranassi may have been a city in Kalašma.” You can see historical knowledge being constructed in real time.

If you’d like to support my work, please pre-order my book Tripping on Utopia: Margaret Mead, the Cold War, and the Troubled Birth of Psychedelic Science or share this newsletter with friends you think might be interested.

And a reminder: if you are in a position to spread the word about the book, review it, or (best of all!) write an article about it, please email me and I’ll personally mail you an advance copy.

Many thanks for reading.

Robert Jay Lifton, Witness to an Extreme Century: a Memoir, 56.

Sidney B. Whipple, "Technocracy is Repudiated by Columbia,” January 24, 1933, Indianapolis Times (United Press International Wire Article).

Osterhammel, Transformation of the World, 913-14.

Mead was not exceptional in her views. Most interwar leftists (and even fascists) were techno-optimists gushing over giant soviet factories and dams. They became skeptical of progress only when the soviets started to mobilize their western sympathizers against America's nuclear arsenal build up.

Technocracy was just a 1920's take on 19th century socialism which proposed running society like a factory. To this day communist regimes like PRC claim that they run society according to the scientific theory of marxism.

Very much like the idea of the social history of AI. It feels like the first drafts of that history--even the best of it like the Atlantic essay and the posts in the Money Stuff newsletter by Matt Levine and in Stratechery by Ben Thompson--are very much focused on the boardroom. I hope someone is writing about the experiences of rank and file OpenAI workers, not as followers of the great leader, but as agents in their own right.

I've always been interested in the resonances of 1930s politics and ideas with the present...this piece has me more jazzed to get my hands on the book.