Lately I’ve been reading a wonderful book called The Reckless Decade: America in the 1890s by the historian H.W. Brands. One takeaway: the people noting the similarities between the 2020s and the 1890s are right. From protectionism to polarization to fears of mass automation, the parallels are sometimes uncanny.

Just to take one example, here’s page 40 of The Reckless Decade, on the writer Brooks Adams, a friend of Teddy Roosevelt who advocated for seeing nations as living organisms:

Already Japan was arising as the dominant power in the Far East; there, Adams asserted, lay the future. Japan’s condition was analogous to Britain’s a century before, namely that of a crowded island country containing much human energy but few natural resources. Yet Japan enjoyed the advantage of being able to learn from the example of the West. Modernizing in the age of steam and electricity, Japan was accomplishing in a generation what had required centuries in Europe and almost as long in America. The center of commerce and civilization had migrated from the European continent across the Atlantic to the United States; just so would it continue west across the Pacific.

“Society is moving with intense velocity, and masses are gathering bulk with proportionate rapidity,” Adams warned. “If so apparently slight a cause as the fall in prices for a decade has sufficed to propel the seat of empire across the Atlantic, an equally slight derangement of the administrative functions of the United States might force it to cross the Pacific.”

Swap out Japan for China, and this is sounding familiar, no?

These and other parallels between the Gilded Age and our present moment — tariffs, presidential bellicosity, etc. — have been well-documented. But there’s a deeper resonance between the 1890s and the 2020s that has gone largely unnoticed: both decades witnessed the emergence of a new kind of technological loneliness.

When we think of media and technology in the 1890s, certain images come to mind: the yellow journalism of William Randolph Hearst, muckrakers exposing runaway corporate power, the serialized novels of H.G. Wells. All were part of a surge in mass communication. The decade was, after all, the golden age of the periodical.

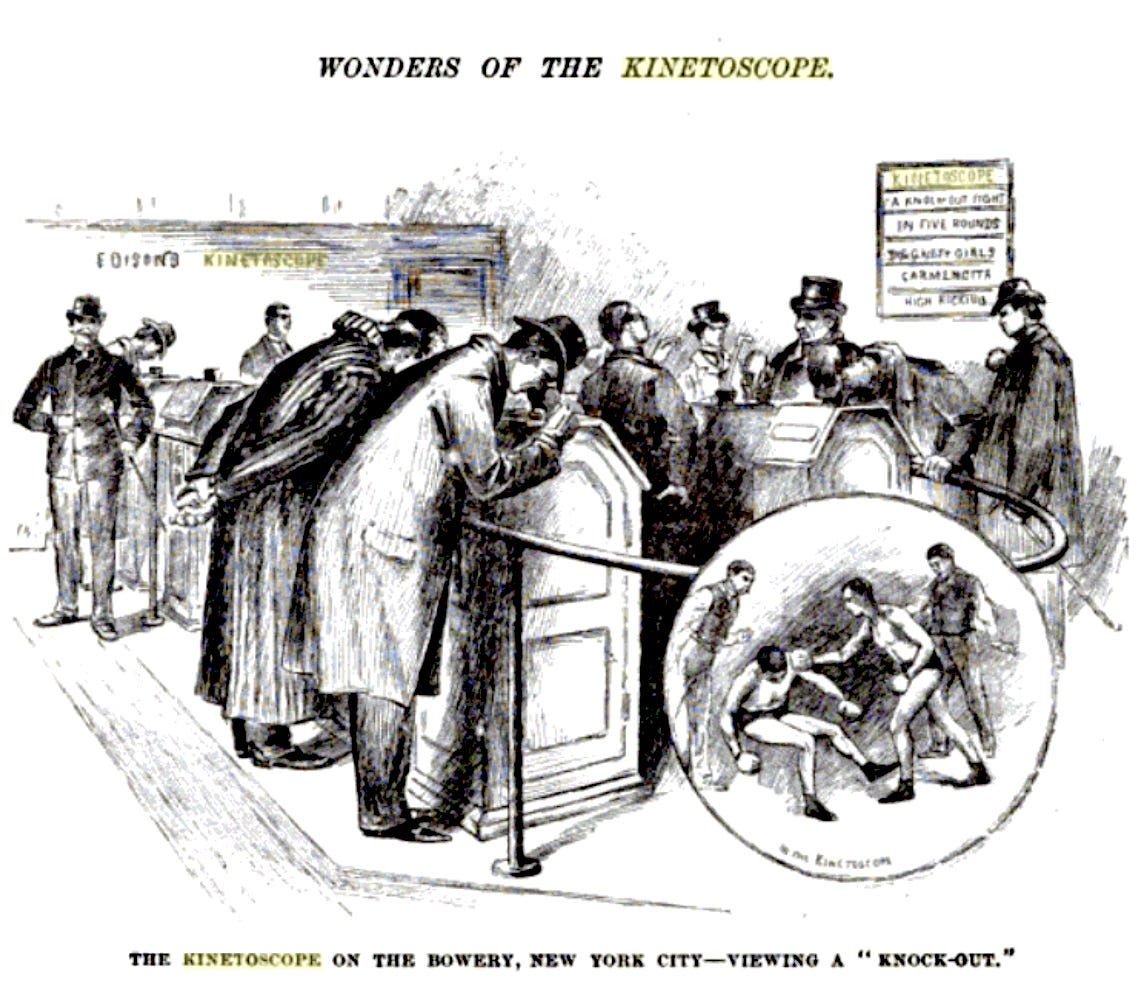

But the most prophetic media innovation of that decade was something less familiar. It was the Kinetoscope: the world’s first commercial motion picture device.

Alone in the crowd

The key thing to understand about the Kinetoscope, the fundamental fact of it, is its loneliness. It displayed a moving picture for a viewership of precisely one.

This was an intentional design choice.

Here’s H.W. Brands on how it came to be:

During the late 1880s and early 1890s, [Thomas] Edison and his researchers tested various methods of exposing film to motion and of playing back the exposures, By 1891 he was ready to file for patents, one for the ‘Kinetograph’ (the special camera that made the exposures) and another for the ‘Kinetoscope’ (the device that played them back).

As was his custom, Edison paid close attention to how he could squeeze the most money out of his invention. One of his researchers had been investigating the possibility of projecting the motion pictures onto a screen for viewing by a large audience. Edison rejected this line of research in favor of the development of his Kinetoscope, a peephole-in-a-box arrangement that required users to watch the film one at a time. Edison reasoned that he could sell more Kinetoscopes than devices that played to hundreds at a sitting.

As you might guess, the new technology lent itself well to pornography.

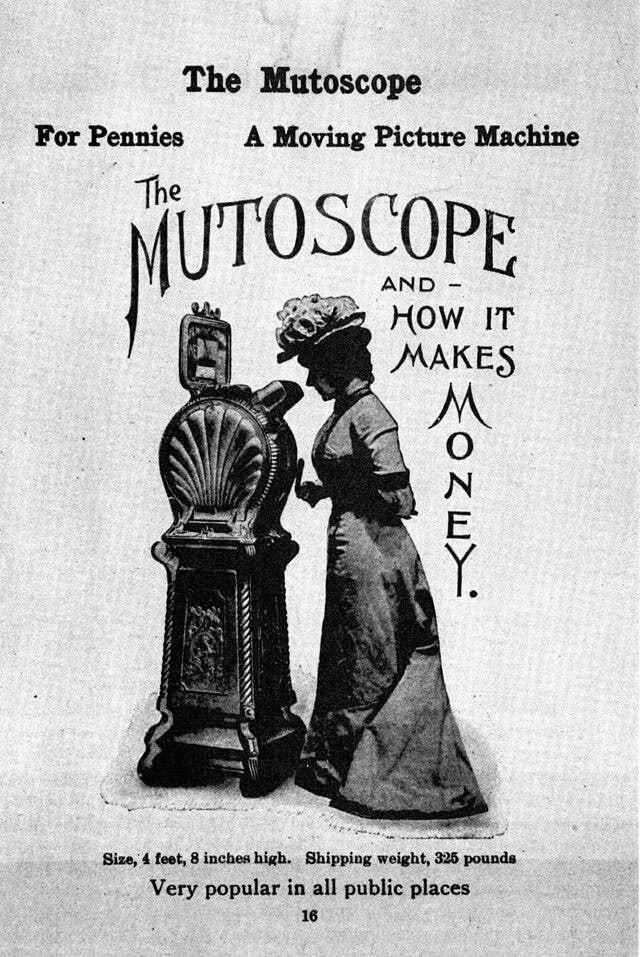

This use case soon spawned a cheaper competitor known as the Mutoscope. In James Joyce's Ulysses, the narrator Leopold Bloom thinks to himself:

“A dream of well filled hose. Where was that? Ah, yes. Mutoscope pictures in Capel street: for men only. Peeping Tom.”

Really though, this sort of thing had far more in common with TikTok — prurient, funny, sometimes violent, and entirely hyperactive — than with pornography as we know it today.

Here’s a random sampling of some of the titles of early Kinetoscope and Mutoscope films to give you an idea:

Monkies’ Feast

Wrestling Ponies

The Drunken Acrobat

Children Playing with Fire

Smoking, Eating and Drinking

A Baby Merry-go-round

Girls Struggling for a Sofa

Some Dudes Can Fight

What else can you call this sort of thing, but “content”? It is eye-catching, eminently consumable, and kind of dumb.1

Writing in the 1890s, William James often described consciousness as having a “fringe,” a ghostly outline just outside of what you could know or experience, but which you still have some vague sense of — like seeing something out of the corner of your eye. What we see happening in the 1890s is the fringe of our daily experience in the 2020s: the earliest formation of a sort of global limbic system that was both mass produced and solitary, interconnected and atomized.

Take a moment to imagine yourself in one of the Mutoscope or Kinetoscope parlors of the 1890s. Perhaps you have heard about “Monkies’ Feast” and want to see what the fuss is about. Staring through the small peephole, you find yourself witnessing motion pictures for the first time. It is addictive, and short. You watch another, then another. You are accompanied by strangers, each staring into their own personalized devices at the same slate of content.

All mesmerized. All paying. But each one consuming the available content at a different rate, making different choices about what to pick, and always — indeed, necessarily — doing so alone.

Does that sound familiar?

If you’ve read this far, please consider a paid subscription. Reader support is essential for allowing me to write Res Obscura — one of the few places online with ad-free, original longform historical writing. You’ll receive the same weekly posts as free subscribers, plus:

Special posts

Quarterly reader Q&As

The warm glow of knowing you are making this newsletter possible

The reckless decade, redux

I've been thinking about the Kinetoscope lately as I observe my daughters first becoming aware of the world in the era of algorithmic feeds and generative AI.

As anyone reading these newsletters regularly has guessed by now, I’m quite interested by AI. I find large language models inherently fascinating — not just because of what they can do or what they might become, but just interesting in their own right, as a new form of technology that behaves and breaks in ways we don’t fully understand.

GPT-3, the predecessor to ChatGPT, was what first caught my attention back in 2020. GPT-3 was weird. It was as if one of the text-based online games I loved playing as a kid had become somehow merged with Wikipedia, and then gone insane in the process.

The first time I realized what LLMs were capable of was when I asked GPT-3 to simulate the experience of playing one of those bygone 1990s AOL games (Gemstone III). It did a great job, cheerfully pretending that the year was 1996 and populating a game world with fake human players pretending to be elves and dwarves.

The only difference: the genuine game, as it existed in the late 1990s, was a simultaneous experience in which several hundred actual humans could be found interacting with one another. What GPT-3 had made was a simulation created for, and inhabited by, exactly one person.

AI, as we are presently building it, is another Kinetoscope.

William James was among those who found Kinetoscopes fascinating in the 1890s. They appear several times in his writings as a reference point for understanding consciousness.

In the most striking example of this, James argues that our conscious experience of reality is shaped by “causal successions of which perception is wholly unaware” — in other words, that there are non-conscious areas of our mind with access to deeper layers of reality. These areas compel us to act or think in ways that exceed our ability to fully understand, much less control.

James writes:

It is as if a baby were born at a kinetoscope-show and his first experiences were of the illusions of movement that reigned in the place. The nature of movement would indeed be revealed to him, but the real facts of movement he would have to seek outside.2

Gertrude Stein (who spent part of the 1890s studying with William James at Harvard) famously called the twentieth century “a time when everything cracks, where everything is destroyed, everything isolates itself.”

Perhaps the Kinetoscope halls of the 1890s were one place where that fracturing began.

As H.W. Brands writes, Edison’s push for the motion picture as a solitary viewing technology failed. It was the film projector and the movie theater that became economically dominant, not the Kinetoscope or Mutoscope.3

But that is not the end of the story. What I find most interesting about this moment in history is the way that a clear and prescient economic logic dictated Edison’s choice. He intentionally engineered his new media device to be usable by only one person at a time. And Thomas Edison was no fool when it came to economic logic.

Brands, writing in 1995, concluded that Edison’s lonely Kinetoscope was decisively and permanently defeated by the mass experience of the movie theater. Films “packed vaudeville halls across America— leaving Edison’s one-at-a-time Kinetoscopes to fill attics and barns and other final resting places for bypassed technology.”

When viewed from the 2020s, though, things look different.

Which approach actually won out? We are all, in a sense, peering into our own personal Kinetoscopes. And I’m thinking not just about the familiar smartphone, but the soon-to-be-familiar personalized AI companion. And beyond and above both, the algorithms that structure and divide our experience of reality. Edison’s vision of monetizing solitude is winning… for now.

It is as if a baby were born at a kinetoscope-show…

Weekly links

• “In the 1930s, video entertainment existed only in theaters, and the typical American went to the movies several times a month. Film was a necessarily collective experience, something enjoyed with friends and in the company of strangers. But technology has turned film into a home delivery system. Today, the typical American adult buys about three movie tickets a year—and watches almost 19 hours of television, the equivalent of roughly eight movies, on a weekly basis. In entertainment, as in dining, modernity has transformed a ritual of togetherness into an experience of homebound reclusion and even solitude.” From Derek Thompson’s excellent Atlantic article about loneliness in 2020s America. Interesting and well-researched throughout, but as you might guess, I think the bit about modernity and entertainment is missing something!

• The largest repository of still images and film from early kinescopes and mutoscopes that I’ve been able to find (Films by the Year)

• “A COMPUTER CAN NEVER BE HELD ACCOUNTABLE. THEREFORE A COMPUTER MUST NEVER MAKE A MANAGEMENT DECISION.” Apparently a quote from an old IBM training manual that cannot be located anymore, but which feels like a message in a bottle thrown from the 1970s directly to 2025 (Simon Williamson)

• “I believe in the art of the Post: Posting is unhinged, unplanned, and unperfected. It involves a kind of lunatic exposure that is perversely admirable. But Posting is one thing and writing is another.” (from “Goodbye to all this” by Becca Rosen)

• John Ganz offering up another set of comparisons between the “tech oligarchs” of the Gilded Age and today.

"If no effort is made to prevent these kinetoscope exhibitions," wrote an 1897 objector to the moral tone of the films they displayed, "they will doubtless be given at every large center of population throughout the country. It is not safe to trust the moral sense of the people to make the enterprise a failure” (source).

From William James, Some Problems of Philosophy (1911), link here.

As late as 1899, though, the directors of the company that produced Mutoscopes were reporting that “the business was going on in a most satisfactory manner,” with subsidiaries in over a dozen countries and plans for ordinary people to “to have their own views taken and have them represented in mutoscopes in their own homes” (source).

The Reckless Decade has been sitting on my backlog for a while now. Thanks for encouraging me to move it up the list.

I have been reading Thoreau's Axe, Caleb Smith's excellent book. The subtitle is Distraction and Discipline in American Culture, which you might guess from the title is about nineteenth-century culture. He reads a passage about attention from Principles of Psychology where James talks about "piercing the shell of lethargy," which is just marvelous.

I take Smith's larger point to be similar to yours. The experience of relating to new cultural technologies started long, long before the iPhone and ChatGPT, and the ideas first expressed more than a hundred years ago, are as relevant today.