There should be more cash prizes for solving historical mysteries

On the Herculaneum scroll and the underrated value of historical knowledge

Twelve days ago, it was announced that a 21-year-old computer science student named Luke Farritor had “became the first person in two millennia to see an entire word” in one of the papyrus scrolls buried within a library in the Roman city of Herculaneum, which was destroyed by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 CE.

Taken together, these scrolls — there are over 1,800 in all, discovered in one of the most lavish of all known Roman houses — are the only surviving intact library from Greco-Roman antiquity.1 The library contains works from ancient authors which were do not exist anywhere else. A poignant example: the Greek philosopher Chrysippus was both famed and prolific in his day, authoring some 700 texts. But aside from stray quotations in the works of others, all of these texts were lost.

… that is, until portions of them were found among the scrolls at Herculaneum. The stakes of this library, in other words, are enormous. Being able to read through all 1,800 scrolls would amount to one of the biggest historical breakthroughs of the century, literally rewriting the history of the ancient Mediterranean.

The trouble is, the scrolls are lumps of carbon. They were torched by volcanic smoke and gas during the eruption of Vesuvius. To unroll them is to destroy them.

Nevertheless, they can now be imaged in remarkable detail, using methods like X-rays and 3-D CT scans.

The progress of this imaging work led to the creation, in 2021, of the Vesuvius Challenge, which promises a series of cash prizes to anyone in the world who reaches certain milestones. These culminate in a $700,000 grand prize which will go to "the first team to read four passages of text from the inside of the two intact scrolls.”

Farritor made international headlines earlier this month when he nabbed the $40k prize for decoding a word. He was joined by Youssef Nader, who won a $10k prize used similar methods to obtain an even clearer image soon after Farritor submitted his work.

The blog post about the find goes into detail about the process, which is fascinating but pretty technical. In brief: earlier imaging in 2019, performed on both unopened and opened fragments, established a “grand truth” of what visible ink looks like in the scan. This allowed researchers to train machine learning models which make educated guesses about patterns in the CT scans of the unopened fragments.

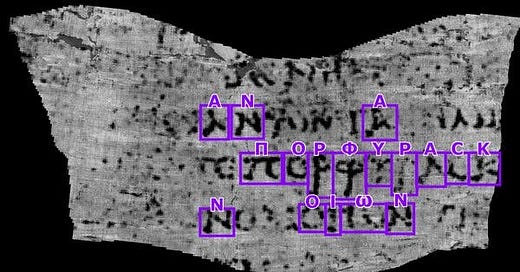

Farritor and Nader were able to use machine learning to recognize patterns in the imaging data which corresponded to letters. The key was the “crackle pattern,” or distinctive texture left by ink.

As the post explains:

[Farritor] began spending his evenings and late nights training a machine learning model on the crackle pattern. With each new crackle found, the model improved, revealing more crackle in the scroll — a cycle of discovery and refinement. He found a few dozen ink strokes — and some complete letters — that could be labeled and used as training data. Before long, the model was unveiling traces of crackle invisible to his own eye. Soon, these traces began to form letters and hints of actual words.

Why does this matter?

For anyone interested in ancient history, this is a big deal. Further refinements of the technique could lead to the transcription of many (most?) of the Herculaneum scrolls. If that happens, it could add hundreds of new texts to the relatively small corpus of writings from Greek and Roman antiquity. It would be a breakthrough for scholars of the ancient world.

But I think this news is important for another reason, too. It’s strong evidence that cash prizes — even relatively modest ones like $10,000 — are effective in producing new historical knowledge.

The offer of material rewards for scientific breakthroughs goes back to the very beginnings of modern science. The Wikipedia page for “Longitude rewards” covers the various eighteenth-century figures — watchmakers, mathematicians, astronomers — who were awarded substantial prizes by the British government for improving techniques for determining longitude at sea (this was extremely important for early modern navies, since it was the only way to navigate reliably). But this concept is older still. As far back as 1567, King Philip II of Spain was offering similar cash rewards for similar challenges relating to improving navigation technology.

But although these “inducement prizes” have a long history when it comes to technological advances, they are almost unknown in the world of historical research. As far as I can tell, the Vesuvius Challenge is the first such prize that is intended specifically to spur efforts to translate, preserve, or decode historical texts.2 (If you know of others, please let me know in the comments).

Can we imagine other situations where a Vesuvius Challenge-esque setup could yield real results?

This was my first attempt at drawing up a list of possibilities:

Decipherment of Linear A. Unlike the riches of the Herculaneum scrolls, the existing corpus of text in this script from Crete circa 1500 BCE is tiny — everything we’ve found could fit on two pages. However, it’s also far older than the scrolls, and thus could potentially add a great deal to our knowledge of the Bronze Age Mediterranean. The big problem here is that we don’t know what language the script was written in, so translating it may not be possible without additional archaeological evidence. Deciphering the Indus script is a related challenge, though it’s still unclear if this is a written script at all (in the sense of encoding spoken language).

Digitization and translation of ancient texts in known, but obscure languages. The Ebla Digital Archive, funded by the Italian government and a consortium of Italian universities, is a great example of what this could look like. It’s a remarkable achievement, offering up not only photos and transcriptions of each of the surviving 4,500-year-old Ebla tablets, but also concordances and full text search (in Sumerian and Eblaite!). But wouldn’t it be amazing if a page like this also contained a translation of the original? And if this sort of thing were duplicated for the thousands of ancient archives written in languages that few people bother to learn?

Decipherment of the Rongorongo script of Rapa Nui (Easter Island). I personally find this the most intriguing of all undeciphered languages.

Thinking about it more, though, I realized that other impactful contributions would be more diffuse and distributed, less about cracking a code than about taking the time to do difficult and self-directed work over lengthy stretches.

For instance, what if there were general prizes for:

Preserving and digitizing endangered archives. A huge percentage of all written texts are not yet digitized. More importantly, a large portion of these have no viable path to being digitized — they simply do not exist in a setting where digitizing texts is possible. Keep in mind that even the United States Library of Congress, which is among the world’s largest and most well-funded archives, has, despite dedicated efforts, not even come close yet to fully digitizing its own collections. Now imagine archives like court records from rural western Nigeria. The British Library, via support from the Arcadia Fund, has a great, long-standing program to preserve and digitize such archives (and FYI, you can currently apply for funding from it!). But these grants of between £15,000 and £150,000 include a complex application process and team-based approach that may be prohibitive to some. I wonder how many new archives would surface if more modest cash prizes of, say, $1,000 to $10,000 were awarded for digitizing and making freely available a set amount of historical manuscripts from anywhere on earth provided they dated to ~1950 or earlier?

Identification of archaeological sites using publicly available satellite data. This is not something I know much about, but it’s really striking to see how effective the internet seems to be at geolocation, on a collective level. Unfortunately, lately that skill is mostly used for warfare porn “OSINT” Twitter accounts rather than things like finding Mayan temples or ancient caravan routes on the Silk Road (although it sometimes helps do that, too).

+ Relatedly: how about a prize for improving methods of LIDAR for archaeological surveying?

Genomic and stable isotope analysis of historical artifacts, like early modern drug jars. This would be my personal pet project if I were a millionaire with time on my hands. Early modern medicines were packed with far-flung ingredients and often mislabeled. But thanks to modern methods of materials analysis, we should in theory be able to figure out the different constituent ingredients even of incredibly complex medicinal compounds like mithdridate. Or, to take another example, isotopic signatures from the claw of a dodo or other species that went extinct in historic times could reveal new information about its diet, origins, and even where it traveled and when.

In other words, it’s not so much about “solving” historical “mysteries” as it is about incentivizing basic historical research.

This lack of wow factor when compared to goals like, say, launching a spaceship, is probably part of the reason why there isn’t a long track record of setting up inducement prizes for history.

Is it a good reason? Not particularly. If you’re wondering why existing funding mechanisms aren’t enough to spur research in fundamental historical problems like decoding scripts or finding new sources, part of the problem is that funding is almost entirely channeled toward people like me: professional historians. One of the distinguishing features of inducement prizes, and part of why they work, is that they bring experts from other fields into the mix. History is not flashy, but it’s of fundamental importance to our species and deserving of ambitious collaborations.

I’m a historian because I believe we humans tend to systematically underrate the value of knowledge from before we’re born. Different ways of being human were available in different time periods — and only in those time periods. When a century or a culture ends, a door closes, forever, on a spectrum of possible human experience. All historians can do is preserve and reconstruct the traces of those experiences.

But there is profound wisdom in those scraps. To extend the memory banks of our species, and to broaden our collective historical memory into cultures not yet well-represented in the written record, seems to me to be one of the better ways that human beings can spend their lives.

In other words, let’s get some inducement prizes for history going!

Source of the Week

A surreal detail from a fresco in the Roman villa at Boscotrecase, built by Agrippa (63 BCE - 15 BCE) and buried by Vesuvius (via Gareth Harney).

Weekly Links

• The first review of my new book Tripping on Utopia came out — and, thankfully, it’s a starred review from Publisher’s Weekly! The key part: “Historian Breen (Age of Intoxication) blends fleet-footed biography with an accessible analysis of mid-20th-century research into ‘psychedelic’ experiences… Breen artfully weaves Mead’s biography with fascinating details of the sprawling psychedelics scene (producers of the TV show Flipper took acid). The result is a riveting exploration of a shadowy episode in 20th-century history.” You can read the full review here or pre-order the book itself here.

• The curiously unknown fate of the Peking Man skull: “In 1941, to safeguard them during the Second Sino-Japanese War, the Zhoukoudian human fossils—representing at least 40 different individuals—and artefacts were deposited into two wooden footlockers and were to be transported by the United States Marine Corps from the Peking Union Medical College to the SS President Harrison which was to dock at Qinhuangdao Port (near the Marine basecamp Camp Holcomb), and eventually arrive at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. En route to Qinhuangdao, the ship was attacked by Japanese warships, and ran aground. Though there have been many attempts to locate the crates—including offering large cash rewards—it is unknown what happened to them after they left the college” (Wikipedia).

• Oregon psychedelic decriminalization goes into effect (Mike Baker, New York Times)

• The history of the Chinese civil service exam. “Using figures provided by Elman, during the Ming dynasty, 1 million regularly took the qualifying tests and, of these, eventually about 400 would make it to the final Jinshi round.” (Yasheng Huang, Aeon)

• “Thokcha (Tibetan: ཐོག་ལྕགས) are tektites and meteorites which serve as amulets.” (Wikipedia)

If you’d like to support my work, please pre-order my book Tripping on Utopia: Margaret Mead, the Cold War, and the Troubled Birth of Psychedelic Science or share this newsletter with friends you think might be interested.

As always, I welcome comments. Thank you for reading!

Wikipedia goes further and claims they’re the “only surviving library from antiquity that exists in its entirety,” but what about the Ebla tablets?

This $10,000 prize for anyone who can find an inscription in the Indus Valley script with “at least 50 symbols distributed in the outwardly random-appearing ways typical of true scripts” is more of a wager about the authors being correct, and not really the open-ended, impartial reward for new discoveries like the sort I am referring to in this post.

There was also the tyrant from Syracuse Dionysis that had a crowdsourcing contest which developed the first catapults in the ancient world. I wrote about this idea of contests or crowdsourcing myself. I'd call them Dionysis Projects, and open them up to the world, like an X Prize

Benjamin nooo! There was no Napoleonic prize for canning food. It’s a total myth!