Why were Belle Époque cities beautiful?

It's not because they were "traditional" or "classical" — in fact it's just the opposite

As a kid growing up in the Bay Area, I often visited San Francisco’s Exploratorium science museum. Back in the 90s and 2000s, it was housed in what I still think is one of the most beautiful buildings in the United States: the Palace of Fine Arts. In my memory, it stands out as a fairy-tale like space that never felt entirely real.

It was never clear to me, when I was eight or nine, just how old the buildings of the complex were. But there was a palpable feeling of otherworldliness to them. We historians love to say that “the past is a foreign country.” These buildings felt like visiting that foreign space of the past.

Much later, it occurred to me that the buildings — the rebuilt remnants from the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition, a World’s Fair designed to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal — were already trying to project a feeling of antiquity on the day they were opened.

As the National Park Service historic registry puts it, the site was “conceived in 1913 by Bernard Maybeck as a forgotten and overgrown Roman ruin.” So really, what we have here is a 1960s restoration of a structure from the Belle Époque period (for purposes of convenience, let’s call that roughly 1870-1920)… which was, in turn, imitating 18th century Europe’s fascination with the ruins of classical Roman antiquity.

Ruins of ruins.

I have been thinking about the contradictions of this 1870-1920 period a lot lately. I’ve begun working in earnest on my new book project, Ghosts of the Machine Age — on the James siblings, Francis Galton, and the origins of the Information Age in the decades preceding World War I — and, in my mind’s eye, I keep finding myself walking beneath those colonnades and beside that lake in late ‘90s San Francisco.

What most jumps out to me now is how modern the people living in this bygone world thought themselves to be, how self-consciously they reflected on it.

For instance, here’s Henry Adams, in his charmingly weird third-person autobiography, The Education of Henry Adams (1907), writing about his visit to the Great Exposition of 1900 in Paris. Adams is led by his scientist friend to the Machinery Hall, where Adams has a quasi-spiritual experience contemplating the future of technology:

[The scientist] led his pupil [Adams] directly to the forces. His chief interest was in new motors to make his airship feasible, and he taught Adams the astonishing complexities of the new Daimler motor, and of the automobile, which, since 1893, had become a nightmare at a hundred kilometres an hour, almost as destructive as the electric tram… Then he showed his scholar the great hall of dynamos... to Adams the dynamo became a symbol of infinity. As he grew accustomed to the great gallery of machines, he began to feel the forty-foot dynamos as a moral force, much as the early Christians felt the Cross. The planet itself seemed less impressive, in its old-fashioned, deliberate, annual or daily revolution, than this huge wheel.

Today, buildings like the Palace of Fine Arts tend to be lauded as examples of a “traditional” or “classical” aesthetic that modernity supposedly abandoned.

For instance, you’ve probably encountered this sort of post online:

This sentiment cuts across ideological lines, from YIMBYs advocating for transit-oriented density to conservative preservationists. There seems to be a collective agreement that urban infrastructure built in the decades just before World War I had a traditional charm we seem to have lost.

But to someone living at the time they were built, like Henry Adams, these sorts of buildings were the ultimate product of technological modernity. They were something close to post-modern pastiche — a society reveling in its distinctly un-traditional ability to smash different elements of the past together into forms aggressively new.

The Belle Époque cities we admire today, from Paris and Lisbon to Rio and Buenos Aires, are filled with similar layers: experimental modernity recast as traditionalist antiquity.1

And that, I think, is part of what makes this era so resonant in the present — and so beautiful.

This architecture is the work of people and societies who were grappling creatively and expansively with technological change.

And that larger point is why I think it’s worth paying heed to the 1870-1920 period as a distinct historical epoch — not just in the realm of aesthetics but in the history of science, technology, and culture, too.

So what is this period telling us?

1: A world just before cars is a better-looking world

Note the “just before.” Go back earlier, to the mid-19th century, say, and you are smack in the middle of the Age of the Horse.

Which is simply another way of saying “the age of constantly stepping in animal dung.” (More on that here, if you are so inclined).

Go forward, say, to the 1930s, and we’re entering the world of Robert Caro’s The Powerbroker, when well-meaning reformers like the young Robert Moses transformed cities into car-friendly construction sites.

One thing that Caro does a great job of showing is the degree to which the highway-building ethos of Robert Moses was rooted in a genuine desire to democratize public space. Moses and other advocates of the automobile saw the growth of suburbs and the clearing of slums as a form of progressive social reform, allowing ordinary people to access public spaces previously denied to them.

Today, though, the car-free urban spaces that people like Moses thought of as old fashioned are celebrated as something we need to restore:

Another way to think about the 1870-1920 period, then, would be “the streetcar era.”

This window of time (between, say, 1881, when the first electric streetcar was trialled in Berlin and 1920, when the first permanent automobile traffic lights were deployed in NYC) marked a still-unequalled high point for car-free transportation.

2: It’s appealing to see new technologies in a raw form

This is a bit counter-intuitive, because it seems to me that a lot of people who valorize the “old days” of cities see post-WWII modernism, especially Brutalist architecture, as a bad thing precisely because it embraced an unadorned reaction to new technological possibility.

But something that emerges really clearly when you look through photos of architecture and cities from the decades before the World Wars is how much it has in common with the basic motivation behind Brutalism — experimentation with novel technological affordances and unadorned materials.

For instance, here is the Machinery Hall from the 1889 Paris Exposition (later used for much the same purpose in the 1900 Exposition, where Henry Adams had his rapturous encounter with the dynamo).

To eyes that have grown up with post-1970s minimalism, this doesn’t look particularly stripped-down. Look at all those girders! All that ornament on the roof!

But when you consider what was technologically possible at the time, when all-metal construction was brand new and extremely difficult, this is a minimalist aesthetic stretched to its very limit.

Here is the original inspiration for this style of building: London’s Crystal Palace of 1851. Today, it looks almost ornate. But when it was built, it would have been a miracle of transparency. The space consciously evokes a medieval cathedral — but smoke-darkened stone has been replaced by clear blue sky.

Granted, any place called something like “The Machinery Hall” or “The Crystal Palace” is of course going to be inordinately technological and future-focused in its design. But even ordinary urban spaces and buildings from these years have a sort of Jules Verne quality to them. You can see the designers actively experimenting with the affordances of new materials and building technologies.

For instance, here is one of my favorite structures in Lisbon, Portugal: the Elevador de Santa Justa (1901). You’ll notice Gothic arches and quite a lot of ornamentation throughout. But they’re subsumed within a form that is entirely a product of new technologies: all-iron construction plus experimental, steam-powered elevators.

The Sugarloaf Cable Car, built in Rio de Janeiro in 1910, is another great example of the era’s experimentation with new technological affordances and pre-car mass transportation systems.

3. Why we can’t (and shouldn’t) go back

It’s tempting to look at Belle Époque architecture and urban planning as a lost paradise we should strive to reclaim. But nostalgia, as always, can distort more than it reveals.

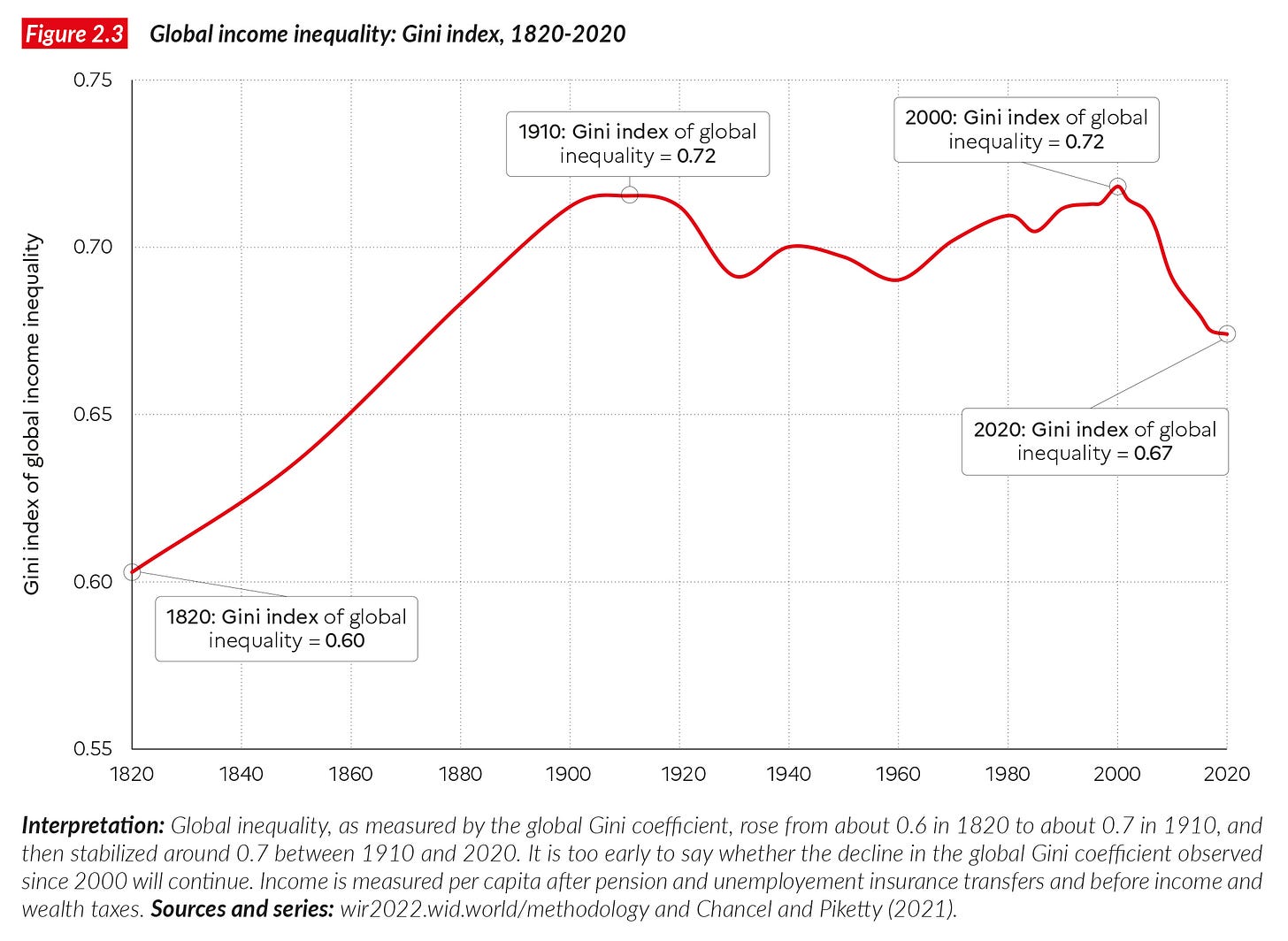

The truth is, for the majority of people living through the 1870 to 1920 period, life was brutal. Social inequality was so extreme that it challenges our modern sense of scale. Economic measures like the Gini coefficient illustrate only part of the story:

Calculating shares of income and how they are distributed in a population is a useful metric for getting a sense of ordinary people’s lives in this era. But so too are factors like “does slavery exist?” and “are women able to vote?” or “what percentage of children die in infancy?”

Take the craftspeople responsible for the exquisite detailing of Belle Époque buildings, for instance. Stucco moldings, hand-carved wooden pediments, intricate wrought-iron balconies — these were all the products of highly skilled manual labor. But how many of these artisans could read a newspaper, cast a ballot, or realistically expect all of their children to live to adulthood? How many had meaningful choices about where or how they lived?

Historian Daniel Immerwahr’s recent article in Past & Present, “All That Is Solid Bursts Into Flame,” drives home another reality: nineteenth-century cities were shockingly prone to catastrophic fires, due in large part to a lack of basic regulations and safety infrastructure. An urban blaze was a routine threat that could level entire neighborhoods overnight.

In this context, the iron-and-glass experiments of the various International Exhibitions and World’s Fairs were not just delightful works of art. They were also very practical attempts to discover new building methods to forestall the risk of catastrophic fire.

And there’s factor at work here, too. When we admire Belle Époque urbanism today, we are largely experiencing spaces designed for, and preserved by, the era’s upper classes. True, some projects like the New York subway or the Paris Métro genuinely improved mass urban life. But the lion’s share of structures we revere today from the “beautiful era” — department stores, opera houses, beaux-arts museums, government buildings, World’s Fair sites — served an audience of wealthy elites, or at best an emergent middle class.

When we think about the charming, car-free boulevards of 1890s cities, in other words, we might remember that they were in some sense like like the locked-down Tate Modern Museum depicted in the great Alfonso Cuarón film Children of Men. Beauty in abundance, but armed guards with dogs just outside.

In short, many of the factors that led to the decline or demise of the “beautiful era” of global cities were, on net, good things for humanity.2

All that said… can we please start building more things like the Palace of Fine Arts?

A note to readers

As I begin work on my new book, I am going to be sharing interesting things I find during my research (like this post) with paid subscribers. I’ve been writing Res Obscura entirely on my own, for free, as a labor of love since 2012. To support that work and receive occasional subscriber-only posts, please sign up as a paid subscriber:

Weekly links

• The Daniel Immerwahr article I referenced above, on fire and capitalism in the 19th century United States, is remarkably good, IMO. It also has one of my favorite opening lines to an academic journal article ever: “In hindsight, yes, the walls of the whale tank should have been thicker. That was regrettable. So was the construction of the snake cage, which, when the fire started, broke apart and sent its inhabitants slithering down the museum stairs and onto Broadway.” Oxford University Press has made the article open access, so you can read the whole thing for free here. Recommended.

• “Rutherford developed the game over four to six weeks in late 1975 as a computerized take on the Dungeons & Dragons role-playing game. Its file was named pedit5, as it was stored in the fifth lesson slot of the school's Population & Energy group. It is considered to be the first example of a dungeon crawl video game and one of the first computer role-playing games” (From the Wikipedia article for pedit5)

Naturally, cities like these (let’s include NYC and London, too) were not entirely or even primarily built in the 1880-1920 period. But a huge range of the attractions in them were. Just to name a few: the Eiffel Tower, the Statue of Liberty, Grand Central Station, Harrod’s, the New York Public Library, and, if we stretch a bit, Big Ben — not to mention the Parisian métro, NYC subway, and London tube. I am using the term Belle Époque in a pretty capacious way in this post, as I think the US-centric idea of the “Gilded Age” is reasonably synonymous with it.

I once looked up my grandmother’s father’s job on the 1920 census. It was listed simply as “laborer.” This was a descriptor that included the people who crafted the gorgeous buildings I’ve shown above. But this was a guy who died in his 50s and who lived without worker protections of any kind.

When I first visited Barcelona I was stunned to hear that the Catalan term for the style of Gaudì's magnificently ornate, curvy, opulent, colourful buildings was... "Modernisme"!

Great article! As they used to say, "I agree entirely!"

I have lived in Chicago, Milwaukee, Minnesota, Spokane, Colorado, and Nebraska. All of my favorite homes (and apartments, and duplexes) are from the 1910s. Across the US, great things were happening in architecture at that time. In two words, it was proportion and details. There were crown moldings, but they were not overdone. The rooms felt like they were the right size: the ceilings were the right height; the windows are the right area, height from the floor and ceiling, and width; The doors were handsome. Ironically, the one space that was like this was a Frank Lloyd Wright duplex in Milwaukee (although a drop ceiling was added which may have thrown everything off).

We also have a magnificent 1915 Steinway piano that absolutely roars.