The leading AI models are now good historians

... in specific domains. Three case studies with GPT-4o, o1, and Claude Sonnet 3.5, and what they mean

This is a post I began writing last year, but several things got in the way: above all, paternity leave. But also my own increasing dismay at the ways that LLMs were being used by students in the classroom. Ask anyone you know in education: ChatGPT has been a disaster when it comes to facilitating student cheating and — perhaps even more troubling — contributing to a general malaise among undergraduates. It’s not just that students are submitting entirely AI-written assignments. They are also (I suspect) relying on AI-generated answers far more comprehensively, not just in their homework but in their daily lives. This has a kind of flattening effect. I’m not alone in noticing the increasingly sameness of student responses to course material. LLMs, which are exquisitely well-tuned machines for finding the median viewpoint on a given issue, are surely contributing to it.

In other words, it’s clear that we will have a turbulent period of change as we figure out how to fit these new capabilities into our existing structures of education. For that reason, I’m not quite as optimistic about how this will go as I was when I wrote this back in fall of 2023:

How to use generative AI for historical research

Last week, OpenAI announced what it calls “GPTs” — AI agents built on GPT-4 that can be given unique instructions and knowledge, allowing them to be customized for specific use cases.

But that’s not the whole story. The headaches that LLMs have caused in the classroom are (I believe) more than counterbalanced by what they can offer as tools for research and self-directed learning. For this reason, I’m now even more optimistic about the long-term impact and utility of AI tools for historical research — and, by extension, for other forms of text or image-based research.

I’m told that OpenAI’s newish o1 model is genuinely helpful and creative when it comes to thinking through open problems in the sciences, especially fields like biology, physics, and medicine. It remains to be seen if it will facilitate any actual breakthroughs. But what’s clear to me is that both o1 and the older GPT-4o model are now almost shockingly good at several core historical skills, and that’s a good thing.

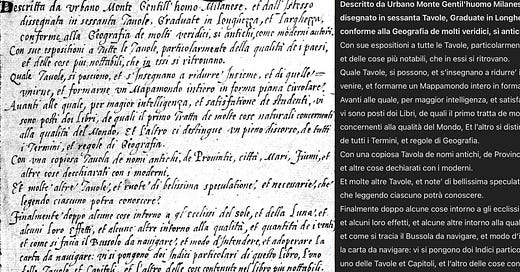

Case study #1: Transcribing and translating early modern Italian

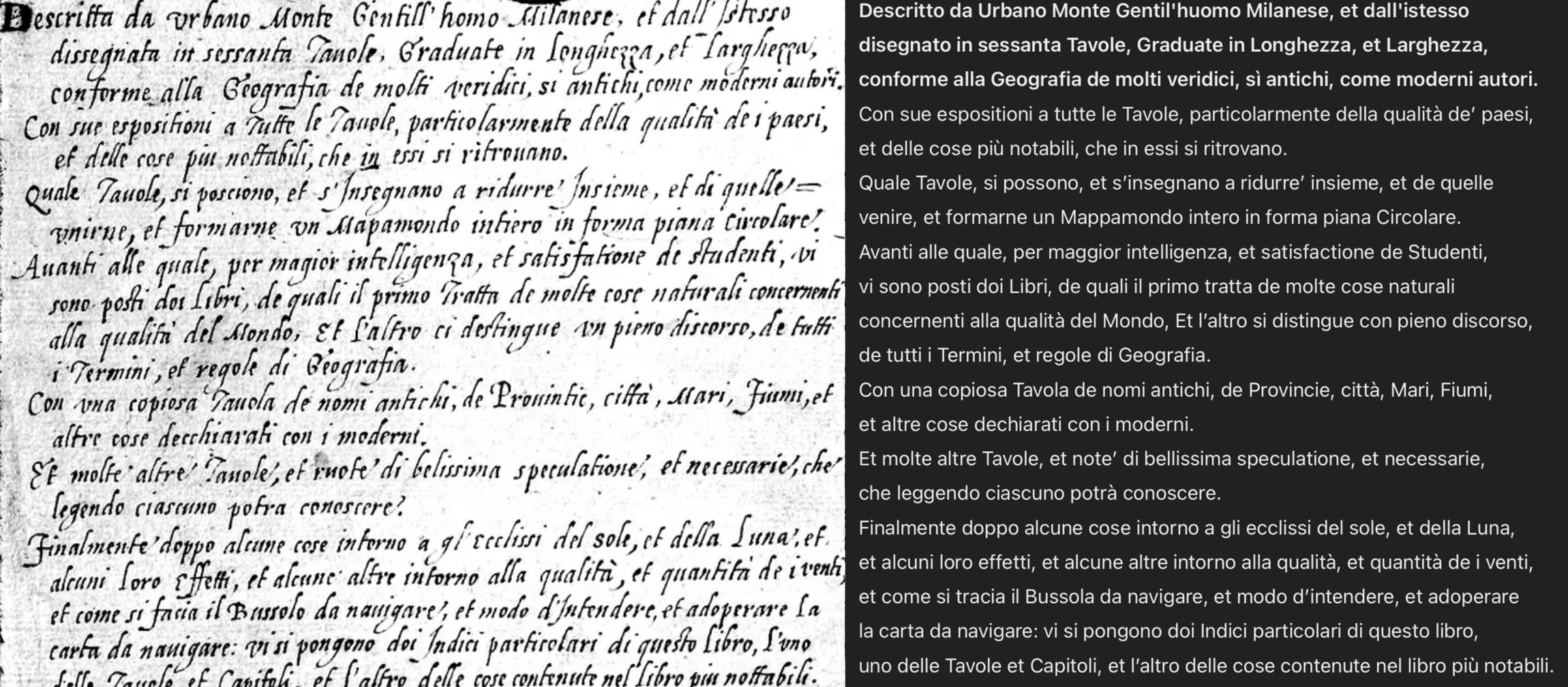

Here, for instance, is how GPT-4o handles the task of transcribing this block of text from Urbano Monte’s world map, written in 16th century Italian cursive handwriting:

This is basically perfect, with the exception of a few small errors (like “disegnato” instead of “dissegnata” in the second line).1

Granted, Monte had unusually legible handwriting, but even “easy” early modern paleography like this is still the sort of thing that requires days or weeks of training to get the hang of.

Likewise, although my knowledge of Italian is not great, I can read it well enough to confirm that the translation it offers is good enough to use for research:

Described by Urbano Monte, a Milanese gentleman, and designed by himself

in sixty tables, graduated in length and width, according to the geography of many reliable authors, both ancient and modern.

With explanations for all the tables, particularly regarding the nature of the regions,

and the most notable things found within them. These tables can be combined and taught to form a complete world map in a circular flat form. Before these, for greater understanding and the satisfaction of students, there are two books: the first deals with many natural matters concerning the nature of the world, and the other is distinguished by a full discourse on all the terms and rules of geography.

It includes an extensive table of ancient names of provinces, cities, seas, rivers, and other elements clarified with their modern equivalents. And many other tables and notes of beautiful speculations and necessities, which anyone reading them will be able to understand. Finally, after some discussions on the eclipses of the sun and moon, and some of their effects, and other matters regarding the quality and quantity of the winds, as well as how to trace a navigational compass and how to understand and use a navigational chart, two detailed indices are provided in this book: one for the tables and chapters, and the other for the most notable contents of the book.

This was provided by a custom GPT I made, the Historian’s Friend, which is a variant of GPT-4o that has a system prompt with some specific directions relating to historical text transcription, analysis, etc. So when asked to provide “historical context” for a translation like this, it knows that it is supposed to cite only the most relevant academic sources.

An excerpt:

Early Modern Cartography and Cosmography

Themes: The creation of large-scale world maps in the early modern era reflects the integration of empirical observation, humanist scholarship, and the legacy of medieval cosmographical traditions. Urbano Monte’s emphasis on combining ancient and modern sources aligns with the Renaissance ideal of synthesizing classical wisdom with contemporary discoveries.

Notable Works for Context:

Brotton, Jerry. A History of the World in Twelve Maps (2012): Examines how maps from different periods reflect cultural and political ideologies.

Harley, J.B., and David Woodward. The History of Cartography (1987–2007): A multi-volume work exploring cartography’s development, including Renaissance mapmaking.

Renaissance Humanism and Classical Continuity

The text’s mention of “ancient and modern authors” reflects Renaissance humanism’s preoccupation with rediscovering and reconciling classical sources with contemporary knowledge.

Key Texts:

Grafton, Anthony. Defenders of the Text (1991): Investigates how Renaissance scholars revived classical knowledge through new methodologies.

Burke, Peter. The Renaissance Sense of the Past (1969): Examines how Renaissance scholars navigated the tension between reverence for antiquity and contemporary innovation.

… and so on.

The upshot: this is pretty much exactly what I would provide for a student trying to learn more on this topic, except it adds texts I should know about, but don’t (for instance, it recommended I read a newish and interesting looking book called The Commerce of Cartography — a genuinely useful tip). Elsewhere in the full response, GPT-4o suggested books which I hadn’t considered as being relevant to understanding a specific early modern map, but which, on reflection, actually are (for instance, Peter Burke book on the Renaissance sense of the past).

Does this replace the actual reading required? Not at all. What it does is aggregate an expert-level knowledge of a topic. Even a year ago, when I requested further reading on a topic, ChatGPT would either invent fake sources or recommend terrible ones (like a History Channel website). That is no longer the case.

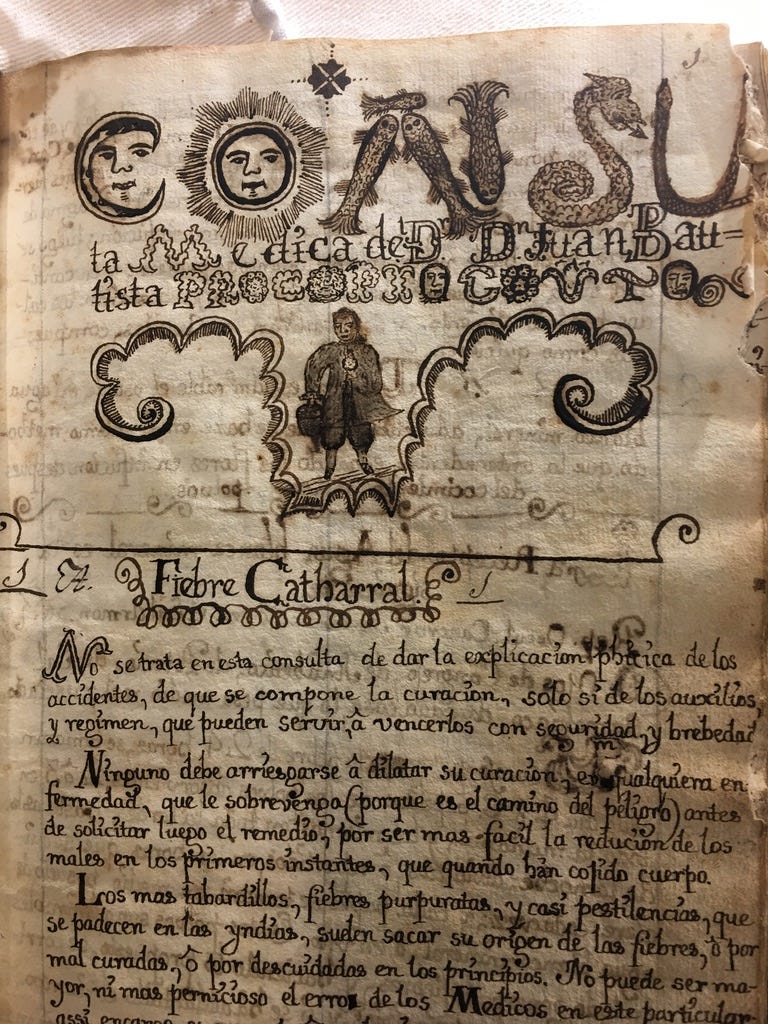

Case study #2: making sense of a strange 18th century medical text

OpenAI’s o1 is the current reigning champ of AI models for reasoning and general-purpose thinking. In my testing, that has proven true when it comes to historical analysis, too. I picked a fairly readable but highly unusual historical source from 18th century Mexico to test it. The following image was provided with no context, just a request to transcribe, translate, and offer a detailed historical and iconographic analysis.

First off, how cool is this book? It’s a page from a manuscript of medical recipes written in 1770s Mexico and now held at the excellent Wellcome Library in London. This is my own photograph from a research trip, but the Wellcome has now fully digitized the book, which you can browse here.

Second, try reading the first lines. Can you make out the words?

o1 gave me the following as a transcription and translation:

Cons[ulta Médi]ca de D[on] Juan Batista Proco[p]io…

Section Title: “Fiebre Catharral”

No se trata en esta consulta de dar la explicación poética de los accidentes, de que se compone la curación, sólo sí de los auxilios, y régimen, que pueden servir a vencerlos con seguridad y brevedad. Ninguno debe arriesgarse a dilatar su curación, en cualquier enfermedad, que le sobrevenga (porque es el camino del peligro) antes de solicitar luego el remedio; por ser más fácil la reducción de los males en los primeros instantes, que cuando han cobrado cuerpo. Los más trabajadillos, fiebres purpurinas, y casi pestilenciales, que se padecen en las Yndias, suelen sacar su origen de las fiebres, y, por mal curadas, o por descuidadas en los principios. No puede ser mayor, ni más pernicioso el error de los Médicos en este particular …

“Medical Consultation of Don Juan Batista Procopio…”

Section Title: “Catarrhal Fever”

Main Text:

“In this consultation, it is not our purpose to provide a poetic explanation of the accidents that make up the cure, but rather to describe the aids and regimen that can conquer them with safety and brevity. No one should risk delaying his cure, in any ailment whatsoever that may befall him (since that is the path of danger), but should instead seek the remedy at once; for it is easier to reduce the harm in the earliest moments, before it has taken root. The worst cases—purplish fevers and those almost pestilential that one encounters in the Indies—often originate in fevers that were improperly treated or neglected at the beginning. There can be no greater nor more pernicious error on the part of physicians in this matter …”

There are, again, a few errors here: it should be “explicación phisica” [physical explanation] not “poetic explanation” in the first line, for instance.2 In this barebones task, I don’t see that o1 is any different from the older GPT-4o model.

Where it shines is in thinking through potential approaches to understanding a text, and also explaining ambiguities.

For instance, here is part of the “iconographic analysis” I asked it for:

This manuscript leaf—judging by its style of calligraphy, Spanish-language text, and references to illnesses “en las Yndias”—almost certainly dates to the Spanish colonial period (potentially the late 17th or early 18th century). The elaborate headings, featuring anthropomorphic suns, serpentine or zoomorphic letters, and the whimsical figure standing beneath the scrollwork, are reminiscent of the flourishing calligraphic tradition in both Spain and the viceroyalties of the Americas during that era. The human figure appears centrally framed by swirling cartouches, suggesting that the artist or scribe wanted to highlight either the author (Don Juan Batista Procopio) or a representative “patient” figure—possibly to symbolize the subject of the medical consultation.

Visual Motifs and Their Possible Meanings

Sun-Faces: The iconography of the sun with a human face was widespread in early modern Iberia and its colonies, often symbolizing enlightenment or divine illumination, but it could also simply be a decorative flourish referencing classical or alchemical imagery.

Serpentine Lettering: The large letter “C” or “S” that coils around the top might allude to the serpent as a medical symbol (thinking of the Rod of Asclepius in classical medicine). Alternatively, it might be purely ornamental.

Human Figure: The small, full-length man in breeches at the center is depicted with care: his stance, attire, and shading could suggest a 17th-century or early 18th-century fashion typical of either a Spanish gentleman or a colonial administrator. The heart or medallion on his chest might be purely decorative, or it could hint at medical knowledge (the seat of the humors) or at a badge of office.

Not bad!

And by the way… what is that “heart or medallion” on the figure’s chest, anyway?

I suspect it’s actually a physician holding (in his right hand) a portable medical chest, and in his left, a urine flask. But what strikes me here is not that the model guessed wrong — it’s that it even noticed such a small detail, and drew attention to it. I mention this one small detail because, to be honest, I had failed to notice it myself.

Although this is not exactly a breakthrough finding, it is quite indicative of the sorts of ways that generative AI can help us do research going forward. It is another, wholly alien pair of “eyes” on a given problem or domain, and that altered perspective can be helpful, even (or especially) when it’s wrong.

Case study #3: generating new historical interpretations

For a final test — comparing OpenAI’s o1 model with Anthropic’s Sonnet 3.5 — I tried giving both a copy and paste from my notes for my new book project, Ghosts of the Machine Age, which is a group biography about the transformations of science and technology in the 1880s through 1910s. Two of the main characters are Francis Galton and William James, so I figured I’d “feed” these two AI models with some direct quotes from James’ letters and works relating to Galton, and then ask it to analyze them, with an emphasis on exploring new paths forward and novel research directions. I also asked it to “perform metacognitive reflection on research paths.”

The results are too long to copy out here, but you can read o1’s full response at this link.

Here’s an excerpt which highlights how o1 leaves behind a “stream of consciousness” (a term William James coined, as it happens) in a sidebar.

Hitherto, it had seemed to me that Sonnet 3.5 was the best AI overall for historical thinking, but o1 clearly thinks at a higher level about the possible uses and interpretations of historical sources.

Here’s the o1 at left and Claude Sonnet at right, both attempting to self-reflect on further paths forward for research on the topic of James and Galton:

Claude was hung up on its own potential flaws, whereas o1 — far more confidently, and far more like a real human historian — began thinking through some legitimate options for archival research to learn more. There is nothing revolutionary here, but for the first time I can see this as a potentially useful interlocutor: someone I can talk to about a new set of ideas or a new research direction.

It’s also interesting to see what happens if you prompt the same o1 model to do something unusual or boundary-pushing. For instance, here is part of what it generated when II asked it for “the most creative, boundary-pushing, or innovative historical arguments or analyses you can formulate based on the sources I provided”:

One could easily read William James’s ambivalent reflections on Galton—and by extension on Pearson and “statistical modernity”—as a polite but profound philosophical revolution in the making. Beneath James’s genial skepticism toward “Galtonian circulars” or “scientific logic” lies a startling proposition: what if the cardinal sin of modern scientific culture isn’t “unreliability,” but rather a flattening of human complexity into numbers that cannot capture the thrumming pulse of individuality?

It then came up with no less than eight different original frameworks for pursuing historical arguments based on these sources.

Here’s one:

1. The Anti-Panopticon of Consciousness

Argument: Galton’s approach—and Pearson’s broader “logical” method—anticipates a kind of proto-panoptic gaze, one that tries to glean “the truth” of humanity from the vantage of big-sample, statistical uniformity. James, however, insists that genuine knowledge of the mind should be irreducibly private and personal. From that vantage, the “self” is not an object but the seat of moral and epistemic agency—capable of forging new truths through introspection and creative will. In effect, James is forging a blueprint for an “anti-panopticon”: consciousness as an irreducible interior fortress that refuses to be pinned down by the numeric lens.

Why This Is Radical: Where Michel Foucault (in Discipline and Punish) identified panopticism as an architecture of total visibility, James’s call for introspective humility subverts that architecture. In this reading, James is the stealth theoretician of privacy in an age obsessed with “averages,” “curves,” and “normal distributions.” Rather than reading James and Galton as simply a difference in philosophical style, one might interpret them as building rival “political technologies” of the mind—Galton’s, to classify and control; James’s, to keep an interior realm off-limits to all but the self.

The above excerpt is… good. I almost want to say depressingly good, because at first glance, it’s fairly close to the level of analysis that I’m currently at with my book project, and it was generated in exactly 5 seconds.

But no: I don’t fear replacement by this kind of thing.

After all (he said, pleadingly) consciousness really is an irreducible interior fortress that refuses to be pinned down by the numeric lens (really, it is!)

Summing up

I realize that some people reading this will probably be thinking around this point “why write a book about William James and the history of science, if the next OpenAI model is likely going to be able to auto-generate a decent approximation of it?”

The answer is that I genuinely do believe that human consciousness and creativity is both an end in itself and a source of value in itself — not something that can be replaced, just as no single human researcher or writer, no matter how brilliant, can replace the work of all the others who may be less skillful or knowledgeable. Especially because it seems to me unlikely that the generic-ness, the median-ness, of LLMs will appreciably change, even as they get shockingly better at meta-reflection and creative thinking.

After all: when you get down to it, o1 talking about a panopticon and Foucault in the above snippet is very, very similar to what a first year history PhD student might produce.

This makes sense: 2025 is, after all, being hailed as the year that PhD-level AI agents will flourish. I can personally report that, in the field of history, we’re already there.

But the architecture of these models, the data that feeds them and the human training the guides them, all converges on the median. The supposedly “boundary-pushing” ideas it generated were all pretty much what a class of grad students would come up with — high level and well-informed, but predictable.

Will that change in the next year or two? Clearly, many people in the AI field and adjacent to it think so. But I favor the possibility that there is an inherent upper limit in what these models can do once they approach the “PhD level,” if we want to call it that. In fact, that’s exactly why I’m writing a book about William James and the machine age: because James, more than anyone, I think, recognized both the irreducibility of even scientific knowledge to a single set of data or axioms, and also understood that consciousness is rooted not just in abstract reasoning but in a physicality, a sensation of being a person in the world.

I don’t discount the possibility that future AI models can be better historians than any human now living — but I think that’s a multi-decade prospect, and one that will probably require advances in robotics to provide sensory, emotional, and social data to go alongside the textual and visual datasets we currently feed these models on.

All that said — yes, these things can definitely “do” historical research and analysis now, and I am 100% certain that they will improve many aspects of the work historians do to understand the past, especially in the realms of transcription, translation, and image analysis. I find that pretty exciting.

If you’ve read this far, please consider a paid subscription. Reader support is essential for allowing me to write Res Obscura — one of the few places online with ad-free, original longform historical writing. You’ll receive the same weekly posts as free subscribers, plus:

Occasional special posts/works in progress

Quarterly reader Q&As

The good feeling of financially supporting something being offered for free.

I had originally written “a couple small errors” here, but it’s actually more like a half dozen. Yet crucially, none of these errors appreciably change the meaning of a word. For example, GPT-4o gives “Descritto” instead of “Descritta” in the first line, but either way, the word means “described” (past participle of descrivere). In many cases, the error simply comes down to GPT-4o wanting to impose modern orthography on the early modern text, like “Gentill'homo” (gentleman) being transcribed in the more modern spelling of “Gentil-huomo.”

Likewise, although I was impressed that it figured out that the glyphs at the top of the page spelled the beginning of the word “Consulta,” it seemed not to notice that the full name of the doctor is "Juan Bautista Procopio Couto.”

I've used AI for similar things. It's very good at transcription and translation and summaries of texts you give it. It does, however, have its limitations for some historical tasks. For example, I've been looking for the source of a half-remembered quote from something I'd read 20 years ago, about Japanese-American relations. I remember the gist of the quote and plugged it in to both Chat-GPT and Claude and both confidently gave me specific sources that were incorrect. So, it's not quite ready for primetime as a research assistant. (In AI's favor, I'm beginning to think the quote doesn't exist, that it was something I thought up myself and attributed to my reading. But, still, the answers were hallucinations.)

You can't really use it yet for deep drill downs in research, as a substitute for doing the reading yourself. It'll give you a better-than-wikipedia summary of a topic, but it lacks the nuance and depth of really good historical research.

I loved this article.

I’m working with Neo-Latin texts at the Ritman Library of Hermetic Philosophy in Amsterdam (aka Embassy of the Free Mind).

Most of the library is untranslated Latin. I have a book that was recently professionally translated but it has not yet been published. I’d like to benchmark LLMs against this work by having experts rate preference for human translation vs LLM, at a paragraph level.

I’m also interested in a workflow that can enable much more rapid LLM transcriptions and translations — whereby experts might only need to evaluate randomized pages to create a known error rate that can be improved over time. This can be contrasted to a perfect critical edition.

And, on this topic, just yesterday I tried and failed to find English translations of key works by Gustav Fechner, an early German psychologist. This isn’t obscure—he invented the median and created the field of “empirical aesthetics.” A quick translation of some of his work with Claude immediately revealed concept I was looking for. Luckily, I had a German around to validate the translation…

LLMs will have a huge impact on humanities scholarship; we need methods and evals.

Would love to join any groups with similar interests to share notes!